First emerging in the early 1920s (Turner & Brown, 2014), the child life profession and its impacts on children and families have grown and evolved alongside pediatric healthcare paradigms and practices (Boles et al., 2020). Some of these adjustments have been clinical in scope, as child life service provision has extended into alternative settings and private practice (Smith et al., 2023). Other areas of growth have been pre-clinical, with the implementation of a formal certification process and modifications to the eligibility criteria for obtaining certification (Child Life Certification Commission, 2022). Each alteration has affected all child life stakeholders, from students to clinical internship coordinators (Sisk et al., 2023), while also ushering in needed adaptations and improvements. Though Certified Child Life Specialists (CCLS) often have an array of professional and organizational networks from which to seek support in times of transition, the same cannot yet be said for emerging child life professionals who are often, but not always, students. In fact, little is known about the experiences and motivations of emerging child life professionals in general, yet this information is critical to anticipating the emerging landscape of the child life profession and the barriers and opportunities that may lie ahead.

Literature Review

Aside from some preliminary descriptive work on very specific subgroups of emerging child life professionals (Adelson et al., 2022; Gourley et al., 2023), much of the current discourse on their needs and experiences entering the child life profession exists in social media, unpublished theses, and conference presentations and posters. The amount of attention the topic has garnered demonstrates high interest, yet there is minimal-to-no data to inform knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices of emerging child life professionals and the CCLS with whom they may someday train or work alongside. As a particularly clear example of this phenomenon, online forums and social media pages may offer information, mentorship, and support for emerging professionals (Adelson et al., 2022). At the same time, these outlets can promote negative narratives or stereotypes without key evidence an audience of consumers needs to draw an accurate conclusion. The latter may then contribute to biased perceptions, unrealistic expectations, or even dampened aspirations for those reading and engaging online.

In the current moment, there are varied and often complex pathways to child life certification depending on access to and achievements in academic and community-based settings (Child Life Certification Commission, 2023). For some emerging professionals, financial resources have been a primary consideration in the pursuit of child life certification (Gourley et al., 2023; Hammond, 2021); whereas, the likely need to relocate for clinical training experiences may be a significant barrier for emerging professionals with family responsibilities and employment commitments (Sisk et al., 2023). Especially pertinent in today’s context, the COVID-19 pandemic also presented difficulties for both practicing child life professionals (Jenkins et al., 2023) and emerging professionals by suspending or constraining clinical training and volunteer opportunities needed for certification eligibility.

Despite these many considerations, barriers, and the dynamic process of the pursuit of the child life profession, students and individuals alike have identified, adapted to, and sought to break down barriers in their journey to child life certification. To understand this phenomenon, it is important to integrate three important educational, motivational, and psychological constructs known to impact goal pursuit across disciplines and contexts: engagement, achievement orientation, and burnout. Though the lay definitions of these words are likely familiar, each is a theoretically grounded and evidence-based factor that has the capacity to affect individuals’ knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and outcomes.

Engagement has been studied in various domains, from professional engagement to academic engagement (Wong & Liem, 2021). Most salient to the experiences of aspiring child life professionals is academic engagement, defined most concisely as a student’s willingness to or likeliness to engage in school activities (Alves et al., 2022). Originally coined by Nystrand and Gamoran (1991), the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral elements of academic engagement have been applied to learners of all ages in different educational contexts, from elementary schools to medical schools (Alves et al., 2022). High levels of academic engagement have been shown to predict better perseverance in the face of barriers, as well as high levels of achievement (Alrashidi et al., 2016).

A well-known typology of personal motivation that can translate across academic and clinical environments is Elliott and McGregor’s (2001) two-by-two model of achievement orientation. Whereas academic engagement is the “what” and “how much” a learner invests in educational activities, achievement orientation is the “why” that drives their expenditure of time and energy. According to Elliott and McGregor (2001), the two-by-two model of achievement orientation dichotomizes learners across two dimensions: achievement goal type (performance or mastery) and achievement direction (approach or avoidance). Performance-oriented learners strive to meet pre-set expectations or thresholds in their learning activities, either out of personal desire to do so (approach) or out of fear of failure or judgment from others (avoidance). On the other hand, mastery-oriented learners seek to master content as much as possible, to achieve beyond pre-set expectations, either out of intrinsic desire to achieve (approach) or, like performance-oriented learners, to avoid failure or judgment (Elliot & McGregor, 2001). Of the four possible achievement orientation types, learners who score as mastery-approach are consistently most likely to persist when they experience difficulty (Alhadabi & Karpinski, 2020) and achieve greater academic and psychological outcomes than their counterparts (Datu & King, 2018).

Presumably most familiar to healthcare professionals is the concept of burnout, which has drawn significant attention during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic (Leo et al., 2021; McKenna et al., 2022). First applied clinically in 1981 by Maslach and Jackson, burnout refers to feelings of emotional exhaustion, self-doubt, and depersonalization associated with chronic workplace stress. Cross-contextual literature has demonstrated that as responsibilities increase, and supports either remain stable or decrease, burnout becomes more likely (Leiter & Maslach, 2016). Burnout, in essence, is the experience of balancing motivation and engagement levels with structural or occupational demands and available supports.

Considered as a conceptually and empirically related trio, academic engagement, motivation, and burnout all help to characterize the experiences of learners and professionals when they encounter difficulty across settings. Although recent research has explored similar constructs in early career CCLS (Ehinger & Bales, 2023; Hoelscher & Ravert, 2021; Lagos et al., 2022; Tenhulzen et al., 2023), little has been done to describe or interpret the experiences of emerging child life professionals as they seek to obtain an internship. Additionally, little research has considered the experiences of this population to identify opportunities for evidence-based supports and systems-level considerations. Therefore, there were two concurrent aims of this convergent, parallel mixed-methods study. The first aim was to examine associations between personal and professional factors (engagement, motivation, and burnout) among aspiring child life professionals. The second aim was to explore the perceptions of aspiring child life professionals related to engagement, motivation, and the barriers and supportive factors they identify as they attempt to enter the child life profession. These two aims were guided by four research questions:

-

What are the relationships among engagement, motivation, and burnout in emerging and current child life specialists?

-

How do emerging and current child life specialists describe the barriers and supports they have experienced while pursuing and participating in the child life profession?

-

How do the barriers and supportive factors reported by emerging and current child life specialists help explain engagement, motivation, and burnout in a larger population of emerging and current child life specialists?

-

What targets for improvement can be identified at the individual and system levels?

Method

The overarching goal of this study was to characterize the experiences of individuals pursuing the child life profession. This convergent, parallel mixed-methods study included a quantitative and a qualitative arm to more comprehensively address the research questions (Creswell & Clark, 2018). Questionnaire data were obtained to characterize emerging child life professionals’ levels of engagement, motivation, and burnout. Simultaneously, individual experiences regarding the pathway to pursuing the child life profession were explored using semi-structured interviews. See Figure 1 for a representation of the convergent mixed- methods study design.

Procedures

Data were collected as part of a larger ongoing cross-sectional study that received exempt-level Institutional Review Board approval (Protocol 211282). Participants for this study were emerging child life professionals recruited via convenience sampling using social media flyers. Social media flyers targeted individuals pursuing child life internships in fall 2021 and spring 2022 and included a QR code to an electronic survey link. Recruitment spanned from August 2021 through January 2022.

Data Collection

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected simultaneously throughout the data collection period. Those interested in participating in the study were first directed to information about the study and the opportunity to provide informed consent electronically, and then to an electronic survey which served as the quantitative measure of the study. It began with a demographic questionnaire as well as questions regarding participants’ academic and clinical experiences. Questions relating to academic experiences explored degree program, status (i.e., in progress or completed), level (i.e., undergraduate, graduate, doctoral, non-degree seeking), and grade point average (GPA). Questions relating to clinical experiences explored history of pursuing child life internship, including number of times applied, affiliation status, and number of experiences and hours working with well and hospitalized children. Following the background questionnaire, participants completed measures of engagement, motivation, and burnout.

Engagement

Engagement was assessed using the University Student Engagement Inventory (USEI) (Maroco et al., 2016). The USEI evaluates the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional dimensions of engagement using a 15-item survey. Participants were asked to indicate the frequency with which each statement applies to them on a scale from 1 = never to 5 = always. This measure has demonstrated strong reliability across all three dimensions and in totality, with Cronbach’s α = .88 for the total measure, .82 for cognitive engagement, .74 for behavioral engagement, and .88 for emotional engagement (Maroco et al., 2016).

Motivation

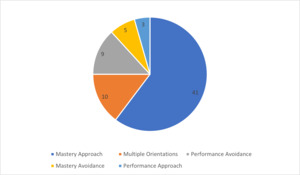

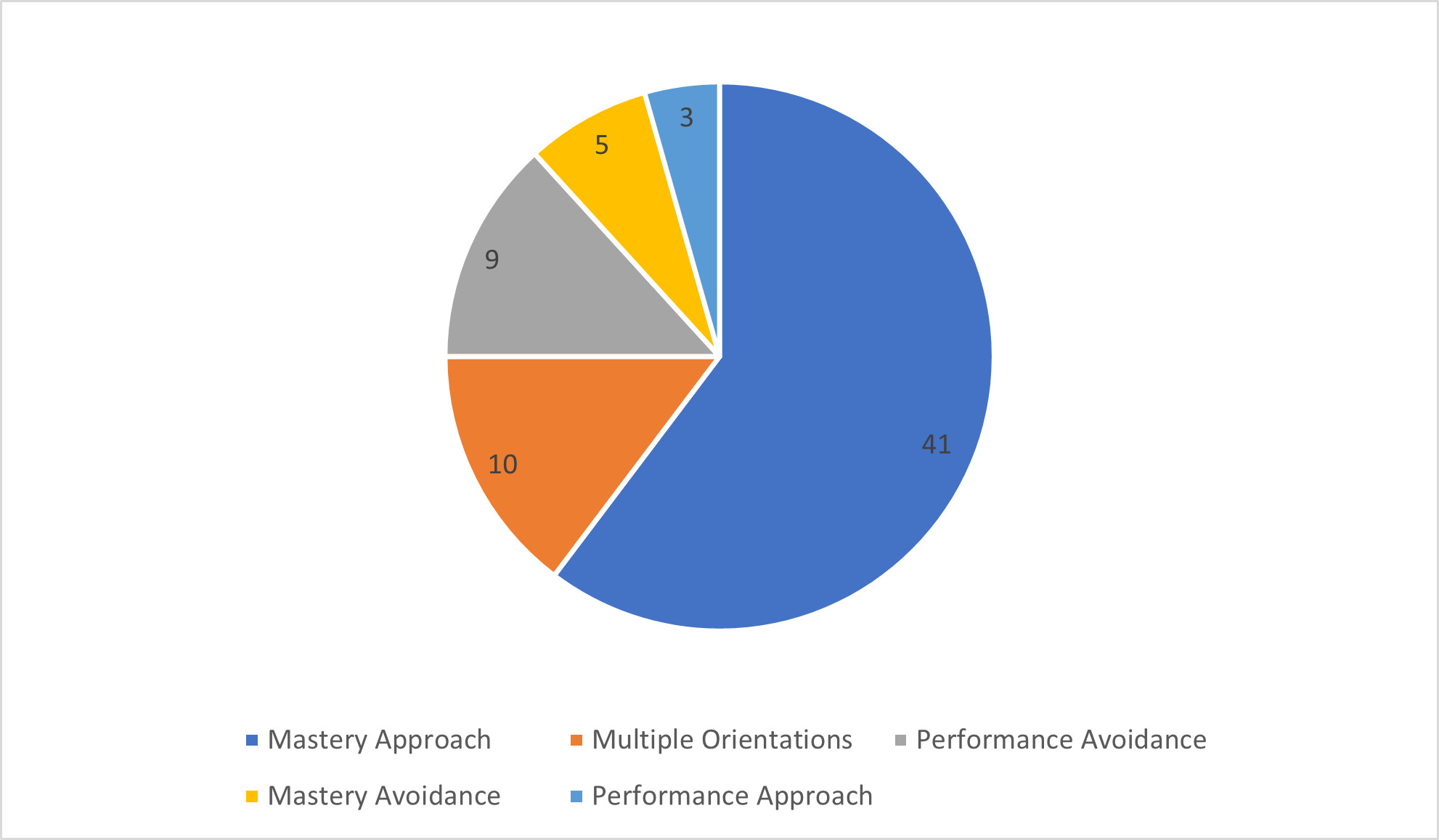

Motivation was assessed using the Achievement Goal Questionnaire (AGQ). Elliot and McGregor (2001) developed a 2 x 2 achievement goal framework, representing how dimensions of competence can be defined and valenced (viewed as either positive or negative). The four achievement orientations are mastery-approach, mastery-avoidance, performance-approach, and performance-avoidance (see Figure 2). The AGQ is a 12-item measure evaluation in which students were asked to indicate the extent to which they believe each item is true for them on a scale from 1 = not at all true of me to 7 = very true of me. The orientation with the highest score indicates that it is the most salient achievement orientation for that student. For the purpose of this study, achievement orientation is referred to as motivation. This aligns with the literature as achievement motivation is most often viewed through the lens of how students pursue their goals. This measure demonstrates strong reliability in each orientation, with Cronbach’s α = .87 for mastery-approach, .89 for mastery-avoidance, .92 for performance-approach, and .83 for performance-avoidance (Elliot & McGregor, 2001).

Burnout

Burnout was assessed using the Maslach Burnout Inventory- General Survey for Students (MBI-GS(S); Maslach et al., 2018). This 16-item measure assesses three domains of burnout, including exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy. Scores are calculated and interpreted separately and the sum of scores does not indicate an overall burnout score. Students were asked to rate the frequency with which they experience certain emotions about their academic work on a scale from 1 = never to 7 = every day. Each of the three MBI-GS(S) scales demonstrate reliability, with Cronbach’s α reported in various groups ranging from .83 to .90 for exhaustion, .74 to .80 for cynicism, and .74 to .83 for professional efficacy (Maslach et al., 2018).

Following completion of the survey, participants were asked to provide their contact information if they were interested in completing a semi-structured interview. The research team emailed individuals who provided contact information and scheduled an interview. Interviews were conducted via Zoom, a HIPAA compliant video conference platform, where only audio information was recorded. Interviews were conducted by the three first authors and lasted 30 minutes to 75 minutes. Interviews were then transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

The quantitative and qualitative data for this study were initially analyzed separately and then together to identify points of convergence or divergence within the data.

Quantitative analysis

The quantitative aim of this study was to characterize the experiences of emerging professionals; therefore, descriptive statistics were reported. Frequencies, with percentages, were used to summarize categorical data, such as age, gender, and methods for funding applications. Means and standard deviations provided averages for continuous data, including GPA and Likert scale items (e.g., scale of worry about funding applications and confidence in getting an internship).

To analyze engagement, a total score as well as scores of subscales were determined through means and standard deviations. Higher scores in the subscales suggest more use of that type of engagement (Elliot & McGregor, 2001). For motivation, mean scores were analyzed for each of the orientation types. Then, participants were placed into the orientation type that they scored the highest mean. Frequencies of the types of orientations were then examined. To assess burnout, means and standard deviations were analyzed for the three domains of burnout. Higher scores indicate higher levels of burnout in that domain (Maslach et al., 2018).

Qualitative Analysis

In conjunction with the quantitative analyses, the 17 interview transcripts were analyzed using an open, inductive coding approach created by Boles and colleagues (2017) that incorporates Moustakas’ (1994) horizonalization and Glaser and Strauss’ (1967) open coding concept. First, each transcript was independently coded by two different graduate students and research team members to cultivate familiarity with the data and crystallize interpretations of each participant’s experiences (Tracy & Hinrichs, 2017). This strategy not only minimizes threats to validity in mixed-methods research, but also allows for unexpected or disconfirming insights to arise early in the analytic process (Creswell & Clark, 2018).

Next, a central code list was created to document all observed instances of each code, and recurrent or overlapping codes were combined into larger categories. These categories were considered through the lens of the study’s focal constructs (engagement, motivation, and burnout) and in relation to one another. From an additional reading of the transcripts, five overarching themes and 14 subthemes were identified. Finally, transcripts were once again reviewed to ensure that these findings were as grounded in the data as possible (Tracy & Hinrichs, 2017).

Integrated Analysis

In convergent mixed-methods research designs, a point of integration for the two databases occurs with a process of comparing the separate quantitative and qualitative results (Creswell & Clark, 2018). A joint display table was developed, organizing key quantitative and qualitative findings alongside one another. This process encouraged a comparison of the findings in order to determine how the results from each phase related to one another. An interpretation of the merged results is included in the results section.

Reflexivity Statement

This study was designed and conducted by investigators who uniquely hold both masters or doctoral degrees and the CCLS credential, with a combined total of nearly 70 years of experience in the academic and clinical training of child life professionals. Thus, academic, clinical, and student perspectives were present in each step of the research study from beginning to end to offer a holistic view of participants’ experiences.

Results

Quantitative Results

Participants

The study recruited 68 emerging child life professionals who applied to the spring 2022 internship cycle, regardless of whether or not they accepted an internship offer. Fifty-three participants completed the survey prior to the spring internship offer deadline; whereas, 15 participants completed the survey afterwards. A majority of the participants were White females between 20 and 29 years old (see Table 1). These findings are expected as the child life profession is predominantly White and female (Ferrer, 2021).

History of Pursuing a Child Life Internship

For a majority of the participants, this was their first time applying to child life internships, with four applying four or more times. A majority of the participants were affiliated with a university/college, applied to 10 or more internship sites, and offered over 150 hours of experience in practicum, hospitalized children, stressful situation, and well children (see Table 2).

Program location, program reputation, and university/college affiliation with the program were deemed as the top three most important factors considered when choosing where to apply (see Table 3). To prepare for internship applications, participants reported using a variety of strategies/resources, including social media (n = 59, 87%), mentor review of application (n = 58, 85%), experienced peer support (n = 57, 84%), academic advisor support (n = 54, 79%), and mock interviews (n = 54, 79%). When asked how confident they were they would receive an internship offer, the participants were only somewhat confident they would receive one, using a scale of 1 (not at all) to 10 (very much; M = 5.85, SD= 2.37).

Costs and Barriers of Applying to Internships. Forty-three percent (n= 29) of participants in this study reported spending between $100 to $249 on applying to internships, with 25 (37%) spending $250 or more (see Figure 3).

On a scale from 1 (not at all) to 10 (very much), participants worried a good bit about affording the costs of the internship applications (M= 6.28, SD= 2.29). The participants used personal savings, adjusted their expenses in general, or adjusted their spending on recreational activities most often to fund the application process (see Table 4).

Outside of costs, the most commonly reported barriers to securing an internship were managing stress and emotions, feeling prepared for the interview, and meeting sites’ expectations during interviews (see Table 5).

Qualities of the Child Life Student

The results highlight some descriptive characteristics of the child life student. Demographics provide evidence that the participants are high achievers, as seen by their GPA (M= 3.82), continued pursuit of higher education (n = 56 at the graduate school level), and amount of experience with children in a variety of settings with most having over 150 hours in the commonly required areas (See Table 1 and 2). Results for engagement, or the way a student engages in their schooling, found that the participants were relatively high in engagement (M= 4.09, SD= .34) and utilized behavioral engagement most often (see Table 6). This type of engagement focuses on students’ participation and conduct in the classroom and extra-curricular activities (Assunção et al., 2020).

When looking at motivation, over 60% of the participants were classified in the mastery- approach orientation style, suggesting they are individuals who focus on interpersonal competence and learning as much about a topic as possible (Elliot & McGregor, 2001; see Figure 4).

For burnout, overall, the participants were high in academic efficacy (feelings of accomplishment, morale, and potential), with moderate exhaustion (feelings of tiring, depletion of interest) and low in cynicism (irritability, negative attitude, depersonalization; see Table 7). These findings suggest that the participants may be feeling more engagement than burnout (Maslach et al., 2018).

Qualitative Results

Participants

Seventeen emerging child life professionals completed the semi-structured interview portion of the study. Like the larger sample of survey participants, interviewees identified as female and were primarily traditional college students pursing a graduate degree, between the ages of 20 and 29 years, with a small subset of individuals between the ages of 40 and 49 years who were pursuing child life as a second career. Participants were also largely White with some representation from Hispanic/Latino, Asian, and Black/African American communities (see Table 8).

Themes

Analysis yielded five themes that appeared to reflect and organize participants’ insights: 1) engagement factors, 2) motivations, 3) burnout factors, 4) sources of support, and 5) barriers to success. Each theme was composed of several subthemes that further characterized participants’ perceptions and experiences (see Table 9).

Engagement Factors. Participants identified three central engagement factors: personal characteristics and experiences, pedagogy, and people. They first described their academic engagement as deeply connected to their perceived traits, such as compassion, empathy, effective communication skills, collaborative spirit, creativity, flexibility, passion for advocacy, high level of child development knowledge, and playfulness (Theme 1, Participant 2). In addition to traits, they described alignment between features of child life practice and their personal work environment preferences; for example, many spoke to preferring a future work opportunity in a healthcare setting that is fast paced, varied from one day to the next, and focused on building relationships with and supporting children and families (Theme 1, Participant 1). Finally in this vein, participants reported on personal experiences with child life services as an engagement factor, whether once receiving child life support as a pediatric patient or seeing the effects of child life work on friends, family members, and community members (Theme 1, Participant 15).

Pedagogy was also identified as a central component of academic engagement for participants in this study. More specifically, they described a desire for interactive, cooperative, and discussion-based learning activities, with a strong preference for those that involve hands-on work or direct engagement with children and families (Theme 1, Participant 11). Some felt that memorization-based tactics or foci decreased their engagement in learning experiences, whereas those that emphasized application, personal reflection, and integration such as clinical case studies, simulation, and clinical practice projects bolstered their sense of engagement (Theme 1, Participant 3).

Last, people were identified as a key engagement factor for this population. Direct interaction with specific stakeholders were reported to increase academic engagement, such as healthcare professionals, child life professionals, patients and families, and opportunities to collaborate with classmates and faculty. When these relationships were perceived as supportive, participants reported feeling more engaged in their child life journey and remarked on feeling more able to access needed information and supports (Theme 1, Participant 14).

Motivations. Participants perceived three factors to affect their motivation for pursuing child life practice: alignment, prevention and promotion, and intended contributions. First, they described deriving motivation from alignment between their personal skills, strengths, and values and the reality of child life work (Theme 2, Participant 15). Next, they spoke to feeling motivated by the capacity of child life work to prevent or mitigate the impacts of trauma on children and families, while also promoting healing and resilience through relationship building and individualized intervention (Theme 2, Participants 2 & 7). Finally, they described feeling motivated to make an array of contributions to families, healthcare systems, and the child life profession through direct intervention, program creation, practice improvement, creative innovations, expending child life into non-hospital settings, and improving care for specific patient populations of marginalized groups (Theme 2, Participant 17). For those participants who were pursuing child life as a second career or had academic emphasis in other disciplines, they uniquely added the ability to translate their skills and experiences from other settings into child life services as a distinct and highly motivating factor (Theme 2, Participant 15).

Burnout Factors. Aspiring child life professionals in this study reported two major factors contributing to their feelings of burnout: the cognitive load of pursuing a child life career and the emotional distress of pursuing a child life career. All participants described challenges trying to access information about the child life certification process that was clear, consistent, and accurate. Additionally, several participants shared concern about the “hidden curriculum” of applying for child life practicums and internships that are not centrally regulated and therefore have variable structures, instructions, philosophies, and requirements (Theme 3, Participant 7). Many participants, including those who identified as “career changers,” reflected on the intensity of managing academic coursework, full-time jobs, family needs, and the cumulative cognitive and time costs associated with each (Theme 3, Participant 11).

The most prevalently discussed element of the themes presented was the dimension of emotional distress participants incurred in their child life journey. Some of this factor was attributed to the cognitive difficulties of pursuing a child life career as noted above. Participants also felt emotional distress due to exhaustion and lack of time for reprieve with difficulty to stay engaged in coursework (Theme 3, Participant 12). Additionally, participants reported distress from their interactions with clinical internship sites. Some reported being “ghosted” by sites who never responded to questions or acknowledged applications or efforts, or receiving generic and unactionable feedback when feedback was sought (Theme 3, Participant 11). Participants also noted a sort of power hierarchy between applicants and professionals that feels devaluing of their experiences. They described meeting application expectations and still failing to receive interview or internship offers, leaving them to conclude that selection processes are subjective. For those who were able to obtain interviews for internships, many described feelings of immense pressure, the need to compare themselves to others in maladaptive ways, high levels of anxiety and exhaustion, and fear of – and the expectation of – exclusion (Theme 3, Participant 6).

Barriers to Success. In addition to the cognitive load and emotional distress associated with pursuing a child life career, participants in this study identified access to information and lack of financial resources as significant barriers to success as an aspiring child life professional. Additionally, they identified the lack of hospital-based volunteering experiences or other direct exposures to child life practice as a considerable obstacle to surmount. In terms of information accessibility, participants specifically found the Association of Child Life Professionals (ACLP) website to be difficult to navigate and expressed multiple experiences of inaccurate or outdated information on individual hospital program websites. They also perceived a lack of a central, consistent, and accurate source of information on the overt and covert components of the child life journey, again stating beliefs in hidden or implicit requirements that are difficult to access without the right supports (Theme 4, Participant 7).

Financially, they described not only the costs of relocation and an unpaid internship experience, but also costs of commuting multiple hours to access hospital volunteer opportunities, and the costs of academic credit hours and expensive application materials (such as transcripts and independent liability insurance policies). Financial supports were reported to be a high priority need, especially for those participants who identified as “career changers,” non-traditional college students, or members of marginalized or under-represented groups. Participants reported a need for financial resources to help with costs of internship application materials, travel costs for internship interviews and site visits, and the costs of food and shelter during a full-time unpaid internship (Theme 4, Participant 4). Those who were also caregivers for their children or family noted the impossibility of maintaining a predictable income while completing child life internships. Many also remarked on the perceived imbalance between the costs associated with achieving child life certification and the reality of compensation for full time child life work or the benefits of investing in resources deemed to make someone a competitive candidate (Theme 4, Participant 17).

Accessing direct exposure to the child life profession was also viewed as a significant barrier. Participants noted the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on available internship and practicum programs, as well as suspended or reduced hospital volunteer programs on their ability to encounter, learn about, and practice play-based skills with hospitalized children and their families (Theme 4, Participant 5). Several reported the difficulties associated with trying to maintain full-time employment and provide for their families while also trying to dedicate multiple hours per week to unpaid volunteer work in the hopes of being more attractive as an internship candidate. Gaining direct experience was also not feasible for participants who needed to juggle these responsibilities while also going out of their way to access facilities that offered the types of experiences that they needed (Theme 4, Participant 14). Many of these barriers to experience were outside the direct control of the participants themselves.

Sources of Support. Participants remarked on seeking various informational and social/emotional supports along the way. As noted in the previous theme, participants reported many difficulties when attempting to access information about the child life career path and tactics for being successful in the overt expectations and implicit requirements of the internship acquisition process. Thus, informational supports were both the most commonly needed and the most commonly used by participants in this study. Specific informational supports described included social media networking groups for students and professionals (run by individuals involved in the child life profession), university-based child life student organizations, academicians and advisors with child life clinical experience, volunteer and/or practicum supervisors in child life programs, classmates, professional development events like regional conferences or webinars, textbooks, and child life research articles (Theme 5, Participant 1). Those who were not currently students or did not have access to an academic program uniquely spoke to needing, and being unable to find, affordable and effective mentors who were knowledgeable about the nuances of the child life career journey.

Social and emotional supports were often sought to both prevent against and mitigate the emotional distress participants reported as a burnout factor. They perceived people such as professors with clinical child life experience, classmates, family members and friends, and even reflection groups as useful sources of social and emotional support (Theme 5, Participant 9). Several participants reported feeling more supported by faculty, classmates, and student organizations as compared to family and friends who were less familiar with the child life profession and its processes.

Integrated Results

A side-by-side comparison of key quantitative and qualitative results provided deeper insight into the experiences of emerging child life professionals. More specifically, the authors noted how taking the quantitative and qualitative results together provides a more robust explanation of instances of engagement, motivation, burnout, barriers, and supports. These interpretations are noted below in the presentation of integrated results (see Table 10).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to describe the engagement, motivation, and burnout experiences of aspiring child life professionals. Overall, it was found that it is difficult to be an emerging professional, and there are multiple barriers in place that impact their academic engagement, motivation, and burnout. Findings help identify evidence-based supports and systems-level considerations for the pathway of the emerging professional.

The quantitative data revealed that emerging professionals are highly engaged individuals who are motivated by a mastery approach (learning as much about a topic as possible). Prior to this study, very little was known about the academic and clinical training of emerging professionals or their engagement and motivation. By examining the characteristics of emerging professionals, the current study expanded the literature to better explain what helps keep emerging professionals engaged, motivated, and protected from burnout. Furthermore, emerging professionals in the current study experienced difficulty managing stress and emotions, as well as financial burdens, as they pursued the profession. As shown in the current study and previous studies, stress can be related to completing the application (Reeves, 2019) or demonstrating in applications or interviews the traits clinical sites are looking for applicants to have including experience, developmental knowledge, and efficient communication skills (Sisk et al., 2023). Like previous studies have shown, emerging professionals often look to social media for support and coping with the barriers to entering the profession (Hammond, 2021).

Qualitatively, participants detailed specific elements of their academic and clinical experiences that impacted their levels of engagement, motivation to pursue child life, and feelings of burnout – all of which can be mapped onto concrete organizational and institutional systems improvements previously suggested (Adelson et al., 2022; Hammond, 2021; Jenkins et al., 2023; Sisk et al., 2023). When participants have access to accurate, comprehensive information, knowledgeable and supportive academic mentors with clinical child life experience, an extensive network of peer and personal support, and opportunities to garner direct exposure to the child life field, they can thrive. However, many of these components are currently inaccessible to today’s emerging child life professionals, thus directly challenging their motivation to pursue the field and their ability to manage their cognitive and emotional distress in the face of unclear expectations and limited opportunities.

The findings from the integrated analysis demonstrated how the quantitative and qualitative findings, when taken together, offer a more complete view of the experiences of emerging professionals and highlight key areas for improvement. The joint display of results (see Table 10) revealed how participants’ reported barriers and supports help to explain the intricacies of engagement, motivation, and burnout. For instance, finances were indicated as a key barrier across both data sets. Integrated analysis further revealed that stress arises not only from the dollar amount of financial burden, but also from the perception that, in order to enter the child life profession, emerging professionals must have more and varied experiences that are hard to accomplish without financial privilege. Therefore, reducing costs is only one suggestion to improve participants’ experiences. It is also important for those already in the profession to manage expectations of experience based on accessibility. Additionally, both sets of data called for increased and clearer information about the pathway to becoming a child life specialist. Because people are a key support for emerging professionals, information should be coordinated with improved partnerships among the child life academicians and clinicians who are guiding emerging professionals. The burden of accessing or providing information should not be placed on any one individual. Taken together, the findings from this study are some of the first documented evidence-based suggestions that will facilitate entry to the child life profession.

Limitations

There are a few limitations to note. For one, although there were multiple racial groups represented in the study, the participants were mostly White and female. Therefore, additional research is needed to continue to examine this topic with more representation from different groups, particularly gender, as there were only females in the current study. Second, this study was conducted soon after the COVID-19 pandemic. There were many impacts of COVID-19 on the child life profession, including limitations to clinical training opportunities. It is important to note that these impacts likely influenced the results. Also, this study was conducted prior to the introduction of the Internship Readiness Common Application Process. With its introduction, internship sites may have changed their procedures for receiving and reviewing applications. This study did not explore group differences among the variables of interest, as it was a descriptive study. Future studies should further examine group differences amongst emerging professionals on engagement, motivation, and burnout, such as those from a child life academic program versus non-affiliated students. Finally, this study looked at the experiences of emerging professionals prior to the internship; therefore, findings should not be generalized to the experiences of emerging professionals during the internship. Future studies should examine this topic in emerging professionals completing an internship.

Implications

The findings of the current study have several implications. For one, aspiring child life professionals need more supports to decrease burnout during their pursuits into the profession. The supports noted included a need for more region-based placement systems like other professions to both promote access and alleviate financial barriers to internship completion and child life certification. In addition, the findings support the importance of child life academic programs having a full-time CCLS in the faculty, as participants consistently noted the importance of having exposure. Such academicians can assist in providing needed information, offering emotional supports, and fostering interactive learning opportunities in child life courses and beyond.

Furthermore, direct clinical experience is important; many participants identified interest in more integrated educational opportunities across academic institutions and healthcare facilities to bolster their learning and provide early and consistent access to clinical engagement. Academic and clinical programs should consider collaborating to offer pre-internship experiences, and academic programs should have pre-internship experiences incorporated into their required coursework to further support emerging professionals.

Finally, the child life profession should recognize the need for a clear path to the profession. The current system does not offer a clear path, which leaves emerging professionals with a lack of information on what to do to enter the profession. This leaves students gathering experiences and seeking support from varied resources in hopes of being able to land an internship, with many being unsuccessful in their attempt. A direct pathway with information clear and accessible about the pathway is needed. A direct pathway could include a child life specific degree requirement and/or a matching system for the internship process. A field specific degree requirement is required for music therapy (American Music Therapy Association, 2023), nursing (Morris, 2023), and social work (National Association of Social Workers, n.d.). The field of child life should continue to examine how a more direct pathway could support emerging professionals in their pursuit of the profession.

Conclusion

This study found that the pathway to the child life profession is a difficult one for emerging professionals. Particularly emphasized were the cognitive and emotional tolls, financial costs, lack of accessible information about the process, and hidden barriers. Clinical internship sites, academic institutions, and the ACLP must reflect on these findings and see how the processes in place may not be supporting the pathway to the profession and are leaving emerging professionals “in a stuck phase” with few opportunities to pursue the profession, despite appropriate engagement and motivation. Emerging professionals are engaged and motivated to serve patients, families, and the profession and deserve supports such as full-time academic mentors, cost-efficient application and internship completion processes, centralized information, and removal of hidden requirements/expectations of internship sites that limit who can access the field.