Illness and hospitalization frequently invoke feelings of uncertainty, anxiety, pain, and loss of control among pediatric patients (Burns-Nader & Hernandez-Reif, 2016; Godino-Iáñez et al., 2020; Lerwick, 2016; Romito et al., 2021). These feelings can have negative impacts on children’s recovery and response to future hospital care (Nilsson et al., 2019). Involving children in making major decisions (e.g., choices about treatment) and minor decisions (e.g., choices about care delivery) can provide children with “power in a powerless environment” (Lerwick, 2016, p. 144). Children’s involvement in decision-making is frequently encapsulated under the term children’s participation,[1] which pertains to “the right of the child to express their views in matters affecting them and for their views to be acted upon as appropriate” (Kennan et al., 2018, p. 1985). In pediatric healthcare contexts, children’s participation in decision-making can help children feel more confident, cooperative, and prepared for medical procedures (Bray et al., 2019; Coyne, 2006; Coyne et al., 2014; Dorscheidt & Doek, 2018).

Child life professionals[2] play an integral role in a variety of healthcare settings as a designated allied healthcare provider that directly delivers psychosocial care to children and families (Boles et al., 2021; Romito et al., 2021). Child life professionals’ focus on enhancing children’s coping and self-advocacy skills can help children develop self-confidence in their abilities to make decisions regarding their health and healthcare. Actively engaging children and families in preparation for medical procedures can also promote children’s social agency and a recognition that children should be involved in all matters concerning them as set out by the widely ratified United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC; Lundy, 2007; United Nations, 1989). Moreover, child life professionals’ skills in developing therapeutic relationships with children and families may help children develop trust in their healthcare providers, creating safe spaces for children’s participation (Carter et al., 2011; Gilljam et al., 2016).

Despite the high degree of alignment between the job responsibilities of child life professionals and children’s participation, there is a paucity of knowledge on how child life professionals experience these rights in practice. Previous studies have primarily focused on the views of nurses and/or physicians on children’s decision-making (Bisogni et al., 2015; Coyne, 2005; Runeson et al., 2002). Based on central findings from a doctoral study (Matthiesen, 2022), the purpose of this critical qualitative study was to explore child life professionals’ perspectives regarding children’s participation in decision-making and how children’s participation processes are shaped by wider contextual (e.g., organizational and socio-cultural) factors.

Literature Review

Despite its documented benefits, the implementation of children’s participation rights, as outlined by the UNCRC (United Nations, 1989), remains challenging in the realities of clinical healthcare practices (Boland et al., 2019; Brady, 2020; Coyne et al., 2014; Coyne & Gallagher, 2011). Pertinent literature points to several important factors that can make implementation complex (Aarthun & Akerjordet, 2014; Boland et al., 2019; Coyne, Amory, et al., 2016; Coyne, O’Mathúna, et al., 2016; Feenstra et al., 2014), including: a) adult attitudes, beliefs and control, b) children’s age and developmental level, c) children’s health status, and d) organizational policies and legal guidelines.

Adult Attitudes, Beliefs, and Control

In pediatric healthcare, children’s participation is complicated by the involvement of multiple stakeholders in decision-making (i.e., children, family members, and healthcare providers; Coyne & Gallagher, 2011). Involving multiple stakeholders in decision-making is encapsulated by popularized shared approaches to decision-making (Van der Weijden et al., 2017). Shared decision-making represents an evidenced-based approach that promotes collaboration between patients (including children), family members, and healthcare providers when making health decisions, in which information is exchanged about the risks and benefits of the decision, as well as patient and family member preferences and values (Boland et al., 2019). In the context of family-oriented pediatric care practices, shared decision-making approaches give rise to significant parental involvement in children’s participation in decision-making (Boland et al., 2019; Coyne et al., 2013). However, children have reported feeling intimidated and neglected when adults control children’s participation in decision-making (Bray et al., 2014, 2019; Coyne, 2008; Coyne et al., 2014; Coyne & Gallagher, 2011; Jeremic et al., 2016; Peña & Rojas, 2013; Zwaanswijk et al., 2011). Healthcare providers (e.g., nurses and physicians) have described an unwillingness to relinquish power and control, uncertainties in managing decisional conflicts, a lack of knowledge regarding children’s communicative abilities, and perceived lack of time to include children in decision-making (Boland et al., 2019; Coyne, 2008; Elwyn et al., 2012; Feenstra et al., 2014; Martenson & Fagerskiold, 2008). While children often desire to participate in decision-making (Coyne, 2005, 2008), views of children as incompetent and in need of protection from the burden of decision-making prevail (Coyne et al., 2014; Sabatello et al., 2018; Toros, 2021).

Children’s Age and Developmental Level

Tailoring the information that children receive in decision-making to their developmental level and literacy needs can facilitate their involvements in decision-making (Boland et al., 2019). However, children’s age is frequently deemed as the most influential factor for assessing a child’s competence to participate in decision-making, which may exclude younger children from decision-making (Coyne et al., 2014; Grootens-Wiegers et al., 2017; Koller, 2016; Toros, 2021). Focusing solely on children’s age also disregards how psychosocial factors can shape children’s participation (Alderson, 2007; Feenstra et al., 2014; Koller, 2016). In assessing children’s decision-making competence, contingencies such as experience, social maturity, and a child’s decision-making preferences may be more salient than a child’s age (Alderson, 2007).

Children’s Health Status

Children’s health status can further influence the role(s) that children, caregivers, and healthcare providers adopt in children’s decision-making processes (Coyne et al., 2014). Particularly when children are too ill or distressed, they may prefer adults to take decisions on their behalf (Coyne, 2010; Coyne et al., 2014). Particularly in pediatric oncology and palliative care contexts, caregivers often take a leading role in making major treatment decisions (Coyne, 2010; Kars et al., 2015). As caregivers in these contexts can experience anxiety, guilt, difficulty coping, and decisional conflict (Allen, 2014; Atout et al., 2017; Kars et al., 2015; Vemuri et al., 2022; Yazdani et al., 2022), some have preferred a physician’s participation in decision-making on behalf of their child with a life-limiting condition (Atout et al., 2017).

Pertinent literature also points to the exclusion of children with disabilities[3] and/or medical complexity[4] in decision-making processes (Franklin & Sloper, 2009; McNeish & Newman, 2002). Despite the varying verbal and non-verbal ways in which children can participate in decision-making (Quaye et al., 2019), a lack of knowledge exists on the extent to which children with complex needs and/or children who use non-verbal communication are being included in participation processes (Franklin & Sloper, 2009).

Organizational Policies and Legal Guidelines

Organizational policies and legal guidelines regarding children’s decision-making can further complicate children’s participation processes (Boland et al., 2019; Brady, 2020). The age of majority in informed consent guidelines vary considerably between countries, provinces, and states – from 12 to 19 years (Alderson, 2007; Katz et al., 2016). In cases when a caregivers’ legal authority conflicts with and/or overrides a child’s decision-making preferences, tensions can arise within a family (Katz et al., 2016). Children’s refusal to consent to medical treatment can also create emotionally and ethically challenging situations (Katz et al., 2016).

The extent to which hospital policies attend to children’s agency can also shape children’s participation (Boland et al., 2019). Policies regarding child- and /or family-centered care reflect an organizational commitment to partnering with families and can facilitate children’s involvements in decision-making (Kuo et al., 2012; Nicholas et al., 2014). However, concerns remain regarding the actual implementation of family-centered care principles in pediatric healthcare practices (Gerlach & Varcoe, 2021; Kuo et al., 2012). To optimize children’s participation across healthcare organizations, there is a need for clear guidelines and policies that reflect all stakeholder views (Coyne & Gallagher, 2011) and offer guidance on how to practice shared decision-making (Dreesens et al., 2019).

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework of this study is grounded in the relational turn of the new sociology of childhood to promote a relational framing of children’s agency and rights (Alanen et al., 2015; Prout & James, 2015). In line with the UNCRC (United Nations, 1989), the sociology of childhood recognizes children as competent social agents with rights to decision-making (Horgan & Kennan, 2021; Ingulfsvann et al., 2020; Mayall, 2002; Montà, 2021). In the relational turn in the sociology of childhood, children’s agency is understood as being shaped by social contexts, including the relationships between children and adults (Abebe, 2019; Alanen, 2011, 2020; Leonard, 2016). In contrast to individualized understandings of children’s agency, relational framings of children’s agency engage with complexity and diversity – including the various verbal and non-verbal ways in which children express their voices (Alanen, 2011; Carnevale, 2020; Facca et al., 2020; Punch & Tisdall, 2016).

Method

This study used a focused and critical ethnographic methodology to understand the rich, complex, and dynamic texture of cultural phenomena (Ritchie et al., 2013). Focused ethnography was selected to explore a specific cultural phenomenon (i.e., children’s participation) among a specific sub-culture (i.e., among child life professionals and hospital directors) in specific contexts (i.e., hospitals in the Netherlands) (Rashid et al., 2019). Critical ethnography was selected to attend to the role of broader systems of power and knowledge in shaping cultural phenomena (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018). Ethical approval[5] to conduct this study was received from the Human Research Ethics Board at the University of Victoria.

Researcher Positionality

In line with an ethnographic methodology, the first author acknowledges her professional experiences as a child life professional in two pediatric hospitals in Canada and her involvements in research and teaching on children’s development. As a White-settler with Dutch and Danish ancestry, she is a fluent Dutch-speaker and has spent time living and practicing in European countries, including the Netherlands.

Both Gerlach and Koller are White-settlers with European ancestry. Gerlach has 25 years of experience as a community-based pediatric occupational therapist and researcher with Indigenous and mainstream pediatric and early years stakeholders in British Columbia. Koller has worked clinically and academically in three pediatric hospitals in the US and Canada. Her extensive clinical experience as a child life professional prepared her for a program of research guided by contemporary views of childhood and the ethical and moral imperatives set out by the UNCRC (1989). Moola is a first-generation settler woman of color with ancestral roots from apartheid South Africa. She has undertaken qualitative scholarship on disabled and chronically ill children’s lives for the past 12 years. She is also a Registered Psychotherapist (Qualifying) and has worked across numerous children’s hospitals in Canada.

Research Site(s)

This study was conducted at two large-scale pediatric hospitals in urban cities in the Netherlands. The Netherlands offers a promising context in which to explore children’s participation rights as children’s decision-making autonomy is a highly valued socio-cultural construct in domestic and civic settings. The Netherlands has ranked consistently high on various international indices, including first on children’s overall well-being (UNICEF, 2020), fifth on the KidsRights Index (KidsRights, 2021), and sixth on the World Happiness Report (Helliwell et al., 2023).

Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Research Methods

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted the participant recruitment strategy and data collection methods used in this study. While the researcher had initially planned to recruit children, caregivers, and child life professionals, ongoing restrictions and high work demands in healthcare settings in the Netherlands prevented the recruitment of children and caregivers during the pandemic.

Participants

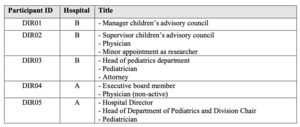

Twelve child life professionals and five hospital directors participated in the study across two hospital sites. The term directors is used to refer to varying job titles, depicted in Table 1.

Participants were recruited through purposeful, third-party recruitment strategy. At each hospital site, a manager of the psychosocial research department or child life department distributed an e-mail to child life professionals containing: (a) information on the study, (b) a recruitment poster, and (c) a private web-link to an introductory video-message. Child life professionals with an interest in participating contacted the researcher directly. In the recruitment of directors, secretaries/assistants forwarded an e-mail message outlining the study objectives and process to directors.

All child life professionals identified as White females. The average age was 39 years and the average length of time practicing in child life was 12 years. Half of child life professionals practiced in an in-patient care setting (e.g., general surgery, oncology, and neurology). Remaining child life professionals practiced in an acute care (e.g., emergency, intensive care) or out-patient setting (e.g., day surgery and dialysis). All child life professionals held an undergraduate degree while one child life professional was pursuing graduate studies.

Data Collection

Individual virtual interviews were conducted with child life professionals and directors. Given the lack of existing research on child life professionals’ roles in children’s participation processes, interviewing was selected as a data collection method to support an exploratory approach (Jain, 2021). Hospital directors were interviewed after child life professionals to gain additional contextual information on the role of institutional policies and legislation in shaping children’s participation rights.

Prior to each interview, participants completed a written consent form. Fourteen interviews were conducted via video-conferencing technology applications (Zoom or Skype). The remaining three interviews were conducted by telephone due to internet connectivity issues (n = 2) and participant preference (n = 1). Interviews ranged from 30 to 80 minutes in length (average duration 60 minutes) and were conducted in Dutch. Separate interview guides were created for child life professionals and directors in consultation with the first author’s doctoral committee members. Before commencing each interview with child life professionals, child life professionals completed a socio-demographic information form to gain insights on their practice and educational background, as well as how participants identify in terms of ethnicity, race, age, and gender.

The interview guide for child life professionals was structured to explore four key categories: a) the meaning of children’s participation (e.g., “How would you describe children’s participation in decision-making?”), b) the role of child life professionals in shaping children’s participation (e.g., “How does children’s participation show up in your daily practice?”), c) facilitators and barriers in children’s participation (e.g., “What helps you support children’s participation in decision-making?”), and d) recommendations for child life practices and the healthcare organization (e.g., “Which supports could the hospital provide to help you include children in decision-making processes?”).

For hospital directors, interview questions focused on: a) the meaning of children’s participation and where it may show up in practices (e.g., “How is children’s participation incorporated in the healthcare institution?”), b) who is involved (e.g., “In your opinion, who plays a role in ensuring children are provided with opportunities to participate in decision-making regarding their care at [hospital name]?”), c) children’s voices (e.g., “Could you tell me about any ways that allow children to have a say in their health/care and/or the development of hospital policies or guidelines?”), and d) recommendations (e.g., “Is there anything you believe the [hospital name] should start, stop, or continue doing?”).

The first author adopted a semi-structured approach to the interviews in which interview questions were ordered to optimise an intuitive and conversational flow (Bearman, 2019). Various types of interview questions were also utilized to gain a deeper understanding of participants’ experiences, including general questions to help initiate the interview, core questions to gain insights on specific domains of interest, as well as planned and unplanned follow-up questions and probing techniques (e.g., silence, echoing, and seeking expansion and clarification) to encourage participants to provide further details when needed (Bearman, 2019).

A secondary ethnographic data analysis method (Roper & Shapira, 2000) involved analyzing seventeen documents (e.g., hospital booklets, pamphlets, policies, guidelines, and web-pages) to provide supplementary contextual data on children’s participation processes.

Data Analysis

In line with the relational framing of children’s agency (Abebe, 2019), the data analysis was guided by a theoretical approach rooted in critical nursing-based scholarship known as “relational inquiry” (Doane & Varcoe, 2021). Relational inquiry attends to “the complex interplay within and between the intrapersonal (what is happening within the people involved), interpersonal (what is happening among people) and contextual (around people and the healthcare situation) dimensions of healthcare situations” (p. 28). This approach was selected to help reveal contextualized and nuanced understandings of child life professionals’ experiences with children’s participation in the Netherlands.

Interview- and document-based data were concurrently thematically analyzed in an iterative manner (Braun & Clarke, 2012). Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim and the first author translated all transcripts and documents from Dutch to English. The data were coded by making notes on each interview transcript and document to identify noteworthy concepts and ideas, as well as patterns between them (Braun & Clarke, 2006). For each participant group, a codebook was created in which quotes and document-based data were categorized into subcodes. Codes were organized into potential subthemes by manually drawing concept maps. During this stage of the messy reality of qualitative data analysis (Clarke & Braun, 2018), the first author iteratively returned to the literature and study objectives and received feedback from the members of her doctoral research committee. Final themes were defined by applying each subtheme back to the raw data (i.e., transcripts and documents).

Results

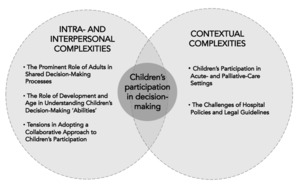

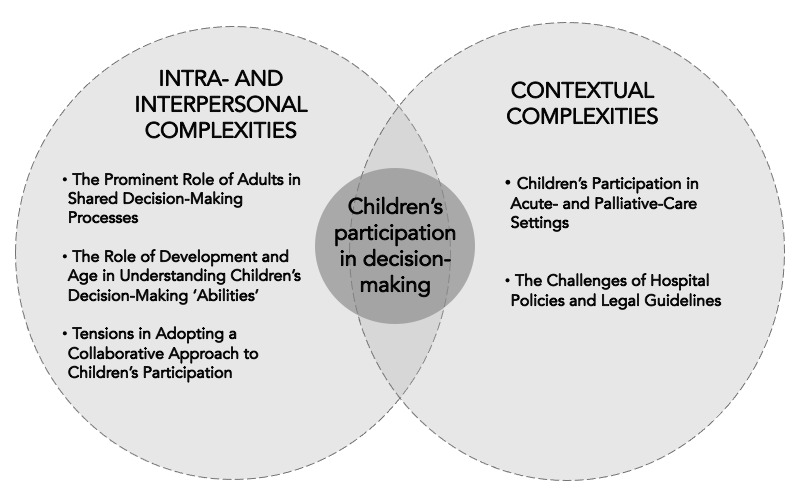

Analysis of the interview- and document-based data suggested that children’s participation in decision-making represented a complex process that was shaped by the relations within and between individuals, as well as wider institutional and socio-cultural contexts. By drawing on a relational inquiry (Doane & Varcoe, 2021) approach, the first author identified five interrelated themes in the data, categorized under intra- and interpersonal complexities and contextual complexities (depicted in Figure 1). In each category, themes are ordered according to their frequency in the data.

The Prominent Role of Adults in Shared Decision-Making Processes

The most prevalent theme pertained to the prominent role of adults in shared decision-making processes with children. All participants’ narratives situated children’s decision-making in “shared decision-making triads with children, parents and [healthcare] providers” (CLP03[6]). A hospital document titled Patient Manifest that was written for children in preparation for hospitalization further underscored this finding:

We will tell you everything about your illness and what we will do about it. We will make those decisions together with you and your parents. Every day when the doctors and nurses visit your room, you can talk about these decisions.

Another booklet titled If Your Child Can’t Decide on Their Own… (depicted in Figure 2), which was written for caregivers of a child with an intellectual disability[7], also emphasized a shared approach to decision-making.

In this booklet, children’s decision-making was framed as a predominantly shared process:

Sharing decision-making between children, parents, and health care providers is a commonly used method to arrive at well-informed decisions. This is particularly important in situations in which there is no clear correct treatment decision and in which there are advantages and (sometimes serious) disadvantages associated with decisions.

The following excerpt from this booklet also speaks to the challenges associated with making complicated shared decisions:

Sometimes, together [parent(s) and healthcare provider(s)] you will know which decision needs to be made. However, other times a decision isn’t so easy to make. Things can become even more complicated when you, as parents, have a very different idea about the right thing to do compared to the doctor or doctors involved.

In a predominantly shared view of children’s decision-making processes, analysis of the narratives of several child life professionals (n = 11) and directors (n = 3) highlighted a noteworthy contradiction. Despite emphasizing that children’s participation is “very much a shared process” (CLP03) through which children can gain motivation and control over their healthcare experience, several child life professionals (n = 6) also associated children’s participation with benefits to their practice. For example, a child life professional stated that “giving children choices gives children the feeling of participating… so that they offer less resistance during medical procedures” (CLP07). Similarly, another child life professional noted that “gaining the cooperation of a child makes our practice easier” (CLP12). Thus, children’s participation in decision-making was associated with benefits to child life professionals’ practices.

From a broader institutional perspective, one director also underscored that the hospital represents “an adult-dominated structure in which adults are needed” in which “real shared-decision-making is still underdeveloped” (DIR04). This finding further emphasized the prominent role of adults in shared decision-making processes.

The Role of Development and Age in Understanding Children’s Decision-Making Abilities

An additional prominent theme pertains to the role of development and age in understanding children’s decision-making abilities related to their health and/or healthcare (n = 15). For example, a child life professional described children’s abilities to be involved in decision-making as “very much tied to the development and age of a child” (CLP04), and a director noted that “the degree to which children contribute to decision-making increases with age, so… it has to be there by age 12” (DIR03).

Many participants described older children as more capable of making big decisions, whereas younger children were primarily offered small decisions:

Look… an eight-year-old child really can’t decide if they even want to have surgery or not… and he generally cannot choose whether an injection is needed but you can let the child choose how they want to undergo the injection so to speak… (CLP03)

In contrast to strict age-based outlooks on children’s decision-making, few child life professionals and directors underscored a customized approach to the decision-making of children with developmental disabilities. As one director articulated:

There are so many different patients around here… maybe a quarter or a third have developmental problems, and one developmental problem is not the same as the other… so you really have to customize the way in which you approach them… (DIR03)

A child life professional also referred to customized non-verbal strategies to support the decision-making of children with developmental delays, including “pointing our thumbs up or thumbs down” (CLP09) or using personal communication or picture books.

Tensions in Adopting a Collaborative Approach to Children’s Participation

An additional theme pointed to tensions in adopting a collaborative approach to children’s decision-making with caregivers and healthcare providers. Most child life professionals (n = 8) described “working as a team” to facilitate children’s participation processes (CLP04). Several child life professionals (n = 8) noted that they “work very well together in healthcare teams” (CLP12) to facilitate children’s decision-making. However, some child life professionals described pediatricians as being “more medically oriented and we’re [child life professionals] more developmentally oriented” (CLP04) – complicating the collaborative approach to children’s decision-making. There were also tensions in child life professionals’ and directors’ self-perceived leadership in facilitating children’s participation. Several child life professionals described their own leadership in standing up for children’s participation:

I think it’s very much our job to… stand up for the child’s participation… and I think that we do that in a more powerful way than other disciplines… but I do see more shifts being made in disciplines… from doctors too… they’re trying. (CLP09)

However, two directors (and pediatricians) underscored pediatricians’ leadership in children’s decision-making. One director stated: “Pediatricians are definitely leaders in patient-centered care… they’re used to involving the child’s parents in the treatment… and I think that other disciplines could learn from them” (DIR04).

Contrasting findings also spoke to the time-consuming nature of children’s participation. A director described children’s participation as “something that just takes a lot of time” (DIR02), whereas the majority of child life professionals dispelled this idea. A child life professional noted: "… one of the biggest challenges is that certain providers think that it [children’s participation] takes a lot of time… but in reality, it probably takes just two minutes longer (CLP06).

Furthermore, few child life professionals (n = 5) described challenges in collaborating with parents in children’s decision-making. One child life professional stated that “parents can speak on behalf of children a lot” (CLP12), while another found that “parents sometimes make decisions for themselves rather than for their child” (CLP12). In such cases, some child life professionals prioritized “thinking of what’s in the best interest of the child” (CLS07), posing questions such as “am I following the child now or am I indirectly following what the parent wants?” (CLP04).

Children’s Participation in Acute- and Palliative Care Settings

Involving children in decision-making in acute (i.e., intensive care and emergency) and palliative care settings represented an additional contextual complexity in shaping children’s participation. In acute care settings, clinical care was described as “quite busy…” (DIR02) with “medical procedures that have to happen” (CLP08). As a result, a child life professional described instances in which children had little to no opportunities to participate in decision-making, also referred to as a false or impossible type of participation. One child life professional underscored this finding:

In cases when children need a feeding tube… for example… you could let them choose which side of the nose they want to have it inserted or what they want to drink with it… but I can imagine that that must sound like a kind of false or impossible participation for the child. (CLP09)

Among children who are “seriously ill” (DIR03) in the context of palliative care, a director also emphasized the prominent role of parents in shaping decisions about a child’s treatment because “while most children with severe cerebral or brain abnormalities cannot make decisions, they do need to be represented… so parents often want to speak on behalf of their children” (DIR03). These findings emphasize the varying complexities that child life professionals and directors associated with children’s participation in acute and palliative care settings, including cases of active termination of life.

The Challenges of Hospital Policies and Legal Guidelines

An additional contextual complexity pertains to the challenges with hospital policies (e.g., family-centered care policies) and legislative guidelines (e.g., UNCRC, the Dutch Youth Law, and Dutch Medical Treatments Contract Act) in facilitating children’s participation. Participant narratives emphasized that “they [policies and guidelines] never specifically show how to do it [include children in decision-making]” (DIR03). A key reason for this was the difficulties in providing generalized guidance on decision-making among all children and families. Due to this challenge, a director emphasized a discrepancy between the legal (age-based) and practical limits of guidelines outlining children’s consent to medical treatment. This finding therefore contrasts with strictly developmental ideas about children’s decision-making capacities described in an earlier theme. The director stated:

The legal limit (for consent) is 12 years but we all know that the involvement of patients in decision-making could and should happen much earlier… age is one element but often it’s not really about age but about the child themselves… So on one hand… there’s the legal limits but there’s also the practical limits… (DIR03)

As a result of these challenges, hospital policies relevant to children’s decision-making were described as “being considered but aren’t really there yet” (CLP06). Moreover, some child life professionals also alluded to being unaware of specific legislations and/or policies that promote children’s rights (e.g., the UNCRC). Children’s rights were broadly described as playing an “indirect role in everyday practices” (CLP09) and some child life professionals preferred to rely more on “personal successful experiences of it [children’s participation] in practice rather than laws, theories, or policies” (CLP10).

Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the challenges and nuances in shaping children’s participation rights in complex pediatric settings (Brady, 2020; Charles & Haines, 2019; Stiggelbout et al., 2012; Tisdall, 2008). From an inter- and intrapersonal perspective, the findings underscore that (a) children often need support (from adults) to participate in decision-making (Feenstra et al., 2014), (b) decisional conflicts may arise in shared decision-making processes, and (c) children can be simultaneously agential and dependent on adults with an entitlement to protection in decision-making (Carnevale, 2020; Carnevale et al., 2017; Horgan & Kennan, 2021), particularly among children with palliative and/or medically complex conditions (Verhagen et al., 2009).

From an organizational perspective, the findings speak to hospital policies’ lack of guidance on how to implement children’s participation rights and child life professionals’ lack of awareness of these rights. Accepting children’s rights at face value in healthcare practices can pose a risk for children’s rights not being actualized in healthcare practice (Brady, 2017; Yigitbas & Top, 2020). In order to facilitate children’s participation in ways that are meaningful, sustainable, and effective (Brady, 2017), healthcare providers and policy makers play a pivotal role in providing children with opportunities to express their views and for these views to be acted upon (Brady, 2020; Lundy, 2007). Organizational policies and procedures should also be optimized to facilitate children’s meaningful rather than tokenistic participation rights (Brady, 2020).

The complexities associated with children’s participation rights provide an impetus to move beyond the somewhat idealized rhetoric of listening to a child’s individualistic voice (Abebe, 2019; Coyne & Harder, 2011; Lundy, 2007; Olszewski & Goldkind, 2018; Sabatello et al., 2018). Relational approaches to pediatric decision-making (e.g., Abebe, 2019; Bell & Balneaves, 2015; Dove et al., 2017; Sabatello et al., 2018) are well-suited to attend to the interdependent social, organizational, and systemic contexts in which healthcare practices and children’s rights are situated (Doane & Varcoe, 2021). Relational approaches to decision-making are underpinned by the idea that “people’s identities, needs, interests, and autonomy are always shaped by their relation to others” (Dove et al., 2017, p. 150). This interdependent viewpoint, therefore, contrasts with more traditional and individualistic understandings of human autonomy in which “people are, in their ideal form, independent, self-interested and rational decision-makers” (Dove et al., 2017, p. 150). From a relational perspective, children’s participation in decision-making is seen as interdependent with contextual factors, such as children’s relationships with adults that may allow children to develop their capacity for exercising self-determination (Dove et al., 2017).

Implications for Child Life Practice

For child life professionals, the findings suggest that children’s participation processes are equally multifaceted and dynamic as are other foundational skills in child life practice, such as assessment (Daniels et al., 2021). Child life professionals are well-versed in assessing the psychosocial well-being of children and families with diverse coping styles, family dynamics, communicative abilities, religious beliefs, and previous healthcare experiences, among other multifaceted factors. In safeguarding ethical care, child life professionals also assess how multifaceted social determinants of health (e.g., poverty and racial discrimination) can shape child and family health outcomes (Koller & Wheelwright, 2020). Facilitating children’s participation in decision-making should also include an individualized approach to assess which contextual factors may facilitate or constrain children’s decision-making (e.g., a child’s health status, child/family individual preferences, and previous healthcare experiences; Daniels et al., 2021; Feenstra et al., 2014). While child life professionals are well positioned to provide individualized care (Piazza et al., 2022; Pillai et al., 2020), a relational inquiry approach (Doane & Varcoe, 2021) can provide a theoretically sound, yet practical lens to strengthen the ways in which child life professionals approach children’s participation from a critical and tailored angle. Relational inquiry (Doane & Varcoe, 2021) can guide child life professionals in asking reflexive questions, such as:

-

What are my beliefs and assumptions regarding children and childhood – do I view childhood as a specific life phase that requires protection or as a time in which agency can be fostered? (intrapersonal)

-

How can the ways in which I am interrelating with children, caregivers, and other healthcare providers shape children’s decision-making? (interpersonal)

-

How can the medical, legislative, and socio-cultural context in which I practice shape children’s decision-making and how can this context help children’s rights come alive in the real world? (contextual)

By widening one’s approach to healthcare situations (Doane & Varcoe, 2021), relational inquiry challenges the prominence of developmental theories that underlie the child life field to promote alternative ways of knowing in child life practice (Koller, 2019). Despite the long- standing history of developmental stage theories in child life practice, child life professionals must be aware of the limitations of standardized developmental theories (Daniels et al., 2021) – including when viewing children’s participation through an age-based lens.

In a collaborative approach to children’s decision-making, relational inquiry (Doane & Varcoe, 2021) can also address the tensions in balancing the medical and developmental viewpoints of pediatricians and child life professionals, respectively. Pediatric medicine is primarily rooted in a biomedical model which purports the idea that health and illness solely concern the physical body and can be studied in isolation. From a strict biomedical perspective, health is “merely seen in the absence of disease” (Rocca & Anjum, 2020, p. 78). Biomedical viewpoints do not attend to the influence of context on health (Rocca & Anjum, 2020). In contrast to a biomedical outlook, child life professionals are primarily educated to attend to contextual factors in shaping psychosocial well being and development. From a relational inquiry approach, different forms of knowledge “only offer a partial picture” (Doane & Varcoe, 2021, p. 51). The findings can therefore accentuate the value of balancing psychosocial and biomedical forms of knowledge to facilitate children’s decision-making processes in healthcare.

Child life educational curricula could also benefit from the integration of: (a) relational sociological scholarship on childhood (Alanen, 2020; Alanen et al., 2015; Wyness, 2013) to emphasize the interdependence between children and adults and (b) a stronger integration of rights-based approaches to children’s participation (e.g., Lundy, 2007). Building awareness of children’s rights in child life practice (Koller & Goldman, 2012) may be particularly salient in the US, as the only United Nations member state that has not ratified the UNCRC (Wagner, 2021). As children’s rights remain “nearly invisible in American social, political, and educational discourses” (Wagner, 2021, p. 7), an impetus is provided for child life educational curricula to integrate rights-based scholarship, frameworks, and approaches in (under)graduate course deliveries (Wagner, 2021).

Limitations

An important limitation of this study pertains to the absence of children’s perspectives and participant observation as an ethnographic research method due to restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. As all child life participants in this study identify as White females, the perspectives of child life professionals who identify with marginalized and equity-seeking communities were also absent. This study therefore does not challenge or de-center the normative narratives of Whiteness (Jensen, 2020), including in child life practice (Koller & Wheelwright, 2020; Lookabaugh & Ballard, 2018). Future research could benefit from (a) exploring children’s participation in decision-making from the perspectives of children, caregivers, and child life professionals with diverse and intersectional backgrounds, (b) recruiting children with disabilities and/or with medical conditions of varying acuities (e.g., palliative, chronic conditions), and (c) using participant observation to capture non-verbal data on the interactions between children, caregivers, and child life professionals in children’s decision-making.

Conclusion

The knowledge generated by this study responds to a gap in knowledge regarding the role and experiences of child life professionals with children’s participation in decision-making. The complexities associated with children’s participation emphasize a gap between how children’s (idealized) decisions related to their health and healthcare ought to be made (e.g., as outlined in the UNCRC) and how they are made in complex pediatric healthcare settings. Through a relational framing of children’s decision-making rights, the findings challenge decontextualized framings of listening to a child’s voice and simplistic notions of choice. Attending to complexities in children’s rights and agency provides a starting point for embedding more critical ways of knowing in child life practice beyond the prevalent reliance on developmental theories. These findings have relevance to a wide array of pediatric healthcare disciplines and policy developments.

Acknowledgements

The first author acknowledges with gratitude the expertise and guidance of her doctoral committee members throughout the completion of this research, including Dr. Lucy Bray for her support and sharing her expertise on children’s healthcare decision-making. Gratitude is also extended to all participants who took the time out of their busy clinical schedules to share their valuable perspectives.

For the purpose of readability and flow of this paper, the term children’s participation is used interchangeably with decision-making, decision-making processes, and children’s participation rights.

In the Netherlands, professionals holding similar job responsibilities to child life professionals are mainly referred to as “medical pedagogical support workers/care providers.”

The authors define disability as including “long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” (United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006).

The authors define medical complexity as representing “complex chronic conditions requiring specialized care, with substantial healthcare needs, functional limitations and high use of health resources” (Cohen et al., 2014, p. 1199).

No additional ethical review board approvals were required from local hospitals in the Netherlands.

For the purpose of study results, child life professional and director participants are identified by the acronym “CLP” and DIR," respectively, followed by their anonymized participant number in the included quotes.

This booklet was published by (Sch)Ouders Ervaringskenniscentrum, Handicap NL, and Emma Kinderziekenhuis Amsterdam UMC (https://www.amsterdamumc.nl/download/boek-als-je-kind-niet-zelf-kan-beslissen.-2019-1.htm).