In the United States, 1.8 million individuals were diagnosed with cancer in 2020 (American Cancer Society, 2020). Approximately 380,000 individuals who have cancer are estimated to be parents of minor children (Weaver et al., 2010). When the cancer patient is a parent, the stress their child faces can lead to a variety of psychosocial challenges, such as anxiety, depression, confusion, anger, and feelings of uncertainty with respect to the outcome of the illness (Osborn, 2007; Semple & McCance, 2010; Visser et al., 2005). The stress of a parent’s cancer diagnosis can disrupt a family’s economic stability and normative routines (Shah et al., 2017), which may lead to a redistribution of household roles and reduce the emotional and physical availability of one or both parents (Grabiak et al., 2007; Phillips, 2015). Psychosocial issues faced by children who have a parent diagnosed with cancer include difficulties with emotions, sleep, energy levels, concentration, academic activities, peer and family relationships, and communication (Chen, 2017; Hauken et al., 2018; Hilton & Gustavson, 2002; Shands et al., 2000; Zahlis, 2001). When ignored, these issues may continue and have negative implications for these children as they become emerging adults (Grenklo et al., 2013; Stoppelbein et al., 2005).

The development and rigorous evaluation of interventions to prevent psychosocial problems from occurring within these families is urgently needed. As such, knowledge of the factors associated with child outcomes is required to design tailored programs and interventions for this vulnerable population. Existing literature suggests factors such as family communication patterns, gender of child and ill parent, and race may impact psychosocial adjustment in families coping with parental cancer (Phillips & Prezio, 2016; Stefanou et al., 2020).

Literature Review

Parent-Child Communication

Open parent-child communication is believed to help families adjust more easily during stressful events such as parental cancer. Open and clear communication within the family and parents who address the feelings and concerns of their children enable children to master distress and prepare for changes in the family due to illness or loss (Hoke, 1997). Open communication within the family may not only lead to more effective coping but may also strengthen the parent-child relationship (Kennedy & Lloyd-Williams, 2009). Relationships between family communication patterns and the psychosocial well-being of children have been found in several studies (Osborn, 2007; Visser et al., 2004). Very young children may have difficulty communicating about a parent’s illness because they lack the cognitive maturity required to understand concepts like cancer (Armsden & Lewis, 1993). Nonetheless, interviews with children have been dominated by emotions such as fear, loneliness, and uncertainty about their parent’s illness (Phillips, 2015; Shah et al., 2017). Children may feel a need to protect an ill parent from their own difficult emotions, leading them to be reluctant about sharing their feelings; they may divert the subject or use tactics of denial to avoid speaking about their parent’s cancer (Phillips, 2015; Phillips & Lewis, 2015; Shands et al., 2000). Difficulties in parent-child communication patterns have been linked to externalizing behaviors for adolescents of all genders who had mothers with a diagnosis of breast cancer (Watson et al., 2006).

Research has shown that open communication patterns between parents and children can act as a buffer against psychological distress resulting from parental cancer (Gazendam-Donofrio et al., 2009). As such, adolescents express a desire for interventions that promote open communication among family members (Phillips, 2015; Welch et al., 1996). Families experiencing parental cancer who display open patterns of emotional expression tend to be less depressed, and families who communicate directly about cancer show reduced levels of anxiety (Edwards & Clarke, 2004). Current parental cancer research relies heavily on samples from the United States and Western European countries; more research is needed to explore how differences in communication styles between individualistic and collectivistic cultures impact coping (Costas-Muñiz, 2012; Loggers et al., 2019).

Gender

Salient differences in children’s psychosocial responses have been found in terms of gender, both of the child, as well as of the ill parent. Adolescent males may wish to hide their parent’s illness from non-family members and are more likely to act out with negative behavior than expressing their feelings verbally (Morris et al., 2018; Northouse et al., 1991). Meanwhile, females may adopt withdrawn or argumentative communication patterns with mothers diagnosed with breast cancer (Ainuddin et al., 2012; Davey et al., 2003; Jeppesen et al., 2016). Compared with adolescent males and younger children of both genders, adolescent females are more depressed, anxious, and likely to report aggressive behavior (Huizinga et al., 2010; Kühne et al., 2013).

Females were more likely than males to be at risk for internalizing behaviors (Huizinga et al., 2010), with adolescent females being most negatively affected (Jeppesen et al., 2016; Osborn, 2007). Females internalizing behaviors were linked to maternal depression (Krattenmacher et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2006). Several studies reported that internalizing problems were more likely for adolescent females with an ill father than for their female peers with an ill mother (Karayağmurlu et al., 2021; McDonald et al., 2016; Thastum et al., 2009).

Race & Culture

Cultural relevance also contributes to the success of psychosocial interventions for families. Davey and colleagues (2003) noted differences between White and African American families coping with parental cancer in terms of emotional experiences, coping strategies, and patterns of seeking social support, although the small sample size of participants in their study made them hesitant to draw any firm conclusions. Research has shown that African American children who had a parent with cancer had unmet needs, such as a lack of access to cancer-related information and reported poor communication with health care providers (Lally et al., 2020). Yet, some of these youth reported posttraumatic growth such as greater appreciation for life, enhanced interpersonal relationships, and an increased sense of personal strengths (Kissil et al., 2010). Davey and colleagues (2013) found that African American families participating in a culturally adapted psychosocial intervention for parental cancer showed greater improvement in parent-child communication than controls. These researchers emphasized the importance of health care providers understanding the historical mistrust and trauma that many African Americans harbor towards the medical and research communities.

Several studies examined strategies used by Hispanic families to cope with parental cancer (Costas-Muñiz, 2012; Loggers et al., 2019). Marin-Chollom & Revenson (2021) focused on whether the cultural values of familismo (familism) and espíritu (spirit) impact Hispanic adolescents’ ability to positively cope with psychological distress. However, Hispanic adolescent and young adult cancer survivors from more acculturated families reported less post-traumatic growth after surviving cancer than their peers who spoke Spanish at home (Arpawong et al., 2013). It was hypothesized that these results could be attributed to decreased parental respect and other family values found in more traditional Hispanic families (Gil et al., 2000). The paucity of research studies including ethnically and racially diverse cancer survivors leads to a lack of insight into the unique needs of these patients and families. More studies examining the nuances of diverse patient populations (including but not limited to black and Hispanic families) have the potential to yield culturally competent implications for family-centered psychosocial interventions.

Despite the large numbers of children affected by a parent’s cancer, few child-focused interventions exist to help families deal with the stress of a cancer diagnosis (Niemelä et al., 2010). Programs of this nature that do exist have demonstrated promising results when evaluated (Bugge et al., 2008; Phillips & Prezio, 2016; Rittenberg, 1996). Most of the existing intervention programs had similar goals and components, including (1) education: educating children and/or parent about cancer; (2) normalization: creating a safe environment which allows them to express their feelings and thoughts as well as provides them with psychological/emotional support; and (3) building on existing strengths: helping them recognize their ability to cope with stressful events and further enhancing their coping skills. These interventions were based on clinical observations of need for such programs, age-related concerns of children, and relevant research findings.

The aim of this study is to identify variables and describe the relationships found between them that predict child outcomes following a psychosocial intervention for families experiencing parental cancer. Identifying these variables will inform development of future studies of interventions for children who have a parent diagnosed with cancer.

Methods

Design

This study was a cross-sectional analysis of secondary data obtained from a multi-year sample of survey results collected between 2009 - 2015 as part of a program evaluation. Participants included in this analysis were limited to English- or Spanish-speaking families in which either the father or mother was diagnosed with cancer and whose child(ren) ages two to 18 years participated in an in-person psychosocial program designed to improve family well-being when a parent has a serious illness. The study protocol for secondary analyses was approved by the University Institutional Review Board – 2015-04-0029.

Intervention and Setting

Wonders & Worries, a non-profit agency, utilizes Certified Child Life Specialists to provide psychosocial support for children ages two to 18 years who have a parent diagnosed with a serious illness. The program uses a manualized curriculum delivered in English and Spanish. The intervention and theoretical model upon which it was based have been previously described in detail (Phillips & Prezio, 2016). The intervention consists of six weekly sessions. To deal with the stress and fear parental cancer brings to the family, these sessions were designed to help children understand cancer, treatment, and its side effects in a developmentally appropriate manner; identify and express feelings related to their parent’s illness; develop positive coping strategies to deal with the changes in the family; and improve communication within the family about the illness (see Table 1).

Children could participate in the Wonders & Worries curriculum through age-appropriate group sessions or individual sessions. In addition, all parents who contacted Wonders & Worries for services received information designed to assist with communication about cancer, promote understanding of children’s reaction to family illness, and support positive parenting techniques. All services were provided by master’s level certified child life specialists with each family being assigned a primary CCLS who would lead their individual or group sessions.

Study Measures and Sample

The survey was administered to parents following their child(ren)'s participation in the Wonders & Worries psychosocial intervention. The original survey was developed by Academic Research Associates, an independent external evaluation firm hired by the non-profit agency. The goal was to develop a measure regarding perceived changes in parenting abilities and changes in children’s behaviors following the intervention. In 2007, a pilot test of the survey was conducted online followed by a field test of 100 families in 2008. Based on the field test, refinements were made to the survey resulting in the 14-question survey used for this study (see appendix A). Families were invited to participate in the survey through the postal service and email (when available). At least two attempts were made to contact each family. Surveys were administered by Nybeck Analytics to an adult family member (once per family) online (93.5%) or provided by trained personnel via telephone (6.5%) for families lacking internet service no later than six months following completion of the intervention. Of the 419 families whose children participated in the Wonders & Worries intervention between January 1, 2009 and June 1, 2015, 39.3% met inclusion criteria (n=165) and completed the survey. There were 287 children within these families who were intervention participants. Mothers were the most common overall survey respondent (90%). The parent-reported nine-item assessment of changes in children’s behavioral issues was rated using a nominal categorical scale from 1 (had no issues and has none after intervention) to 5 (had issues that are still the same after the intervention; Appendix A).

Statistical Analysis

Demographic information was tabulated. The proportions of children who had parent-reported behavioral issues in nine areas prior to participation in the Wonders & Worries intervention were determined. Cross tabulations with Pearson’s Χ2 were performed to compare results of these pre-existing behavioral issues between mothers with cancer and fathers with cancer. The subsets of children who had parent-reported pre-existing behavioral issues that improved following intervention were determined. Cross tabulations with Pearson’s Χ2 were performed to compare results of improvement in behavioral issues between mothers with cancer and fathers with cancer.

A logistic regression model was constructed for each of the nine behavioral issues to evaluate the association of various predictors on the prevalence of the behaviors. Covariates included in these models were child sex, child age, race, parent with cancer diagnosis, time between cancer diagnosis and intervention, financial difficulty after diagnosis, and annual income.

To evaluate the association of predictors of the nine behavioral issues (improved vs. not improved), logistic regressions models were constructed using child age, child gender, race, parent with cancer diagnosis, time between cancer diagnosis and intervention, ability of child to communicate about the illness, annual income, individual support, and group support as covariates.

Results

Demographic characteristics of families and children are presented in Table 2.

Families (n = 165) who participated in the Wonders & Worries intervention were largely White (64.9%) with an annual income greater than $50,000. The parent diagnosed with cancer was most frequently the mother (66.7%). Most of these families presented to obtain services within three months of the cancer diagnosis, and 16% of these families experienced the death of the ill parent. Financial difficulty following the diagnosis of cancer was reported by 40.6%. The largest group of participants was five to 11 years (51.9%) followed by 12 to 18 years (39.4%).

The unadjusted proportions of children reported by a parent to have nine behavioral issues prior to participation in the intervention are shown in Figure 1. The range of issues reported by families in which the mother was diagnosed with cancer was 9.7% (eating problems) to 76.4% (feeling anxious or nervous). Similarly, the range of issues reported by families in which the father was diagnosed with cancer was 12.9% (eating problems) to 72.4% (difficulty communicating about the illness). Families more frequently described children with ill parent relationship difficulties if the father was ill, 48.8% vs. 31.3% (p = .006). Families in which the mother was ill more frequently reported children feeling insecure at home, 51.6% vs. 37.9% (p = .048) or feeling anxious or nervous (p = .024; See Figure 1).

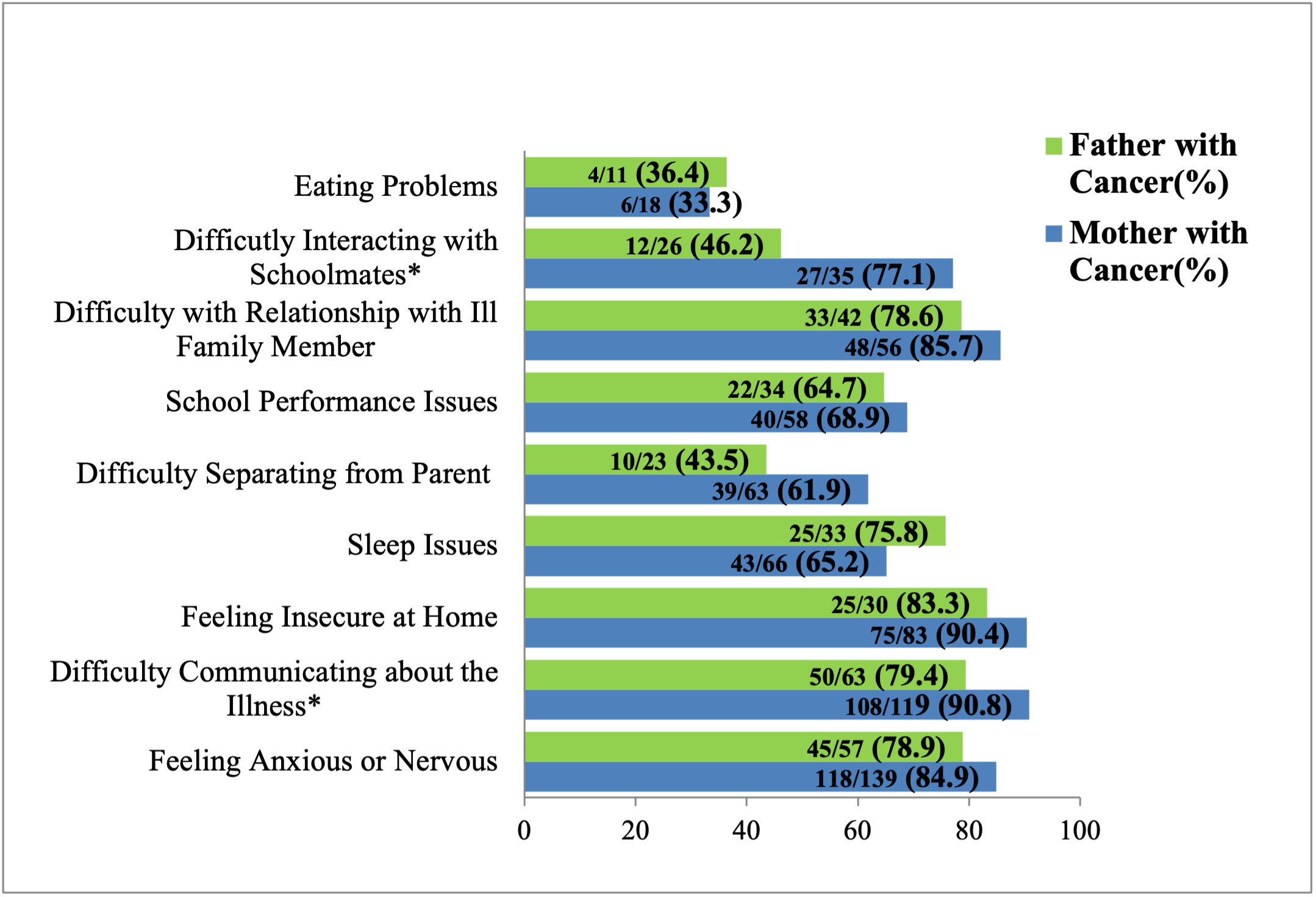

The unadjusted proportions of children reported by a parent to have pre-existing behavioral issues that improved following the intervention are shown in Figure 2. The range of improvement of behavioral issues for families in which the mother was diagnosed with cancer was 33.3% (eating problems) to 90.8% (difficulty communicating about the illness). The range of improvement of behavioral issues for families in which the father was ill was 36.4% (eating problems) to 83.3% (feeling insecure at home). Families in which the mother was diagnosed with cancer more frequently reported improvements of children interacting with schoolmates, 77.1% vs. 46.2% (p = .013) and communicating about the illness, 90.8% vs. 79.4% (p = .031; See Figure 2).

Results of logistic regressions that related the proportion of children who had nine behavioral issues before participation in the intervention to demographic characteristics are shown in Table 3. Families who experienced financial difficulty were significantly more likely to report the presence of sleep issues, p = .002, OR = 2.48, 95% CI [1.38,4.46], eating issues, p = .018, OR = 3.21, 95% CI [1.21,8.48], children feeling insecure at home, p = .001, OR = 2.82, 95% CI [1.5,5.27], children who were anxious/nervous, p < .001, OR = 4.68, 95% CI [2.28,9.63], children having difficulty with their relationship with the ill parent, p < .001, OR = 3.33, 95% CI [1.79,6.19], and child difficulty separating from parent, p = .024, OR = 2.03, 95% CI [1.1,3.76]. Hispanic/Latino(a), African American, and other families were less likely to report problems with school performance, p = .02, OR = 43, 95% CI [.21,.87], or children feeling anxious/nervous, p = .018, OR = 38, 95% CI [.17,.85], compared with White families. Families with annual incomes between $50,000 to $99,999 were significantly less likely to report child sleep issues, p = .03, OR = 46, 95% CI [.22,.93], or child anxiety/nervousness, p = .046, OR = 43, 95% CI [.18,.99], compared with families who earned less than $50,000 per year. Children were more likely to have difficulty interacting with schoolmates, p = .031, OR = 2.08, 95% CI [1.07,4.04], and with relationships with the ill parent, p = .004, OR = 2.6, 95% CI [1.36,4.96], if the father had cancer. Eating issues were more likely, p = .032, OR = 2.65, 95% CI [1.08,6.51], when families participated in the intervention more than three months following the cancer diagnosis. Children ages 12 to 18 were more likely to have difficulty with the relationship with the ill parent, p = .029, OR = 3.94, 95% CI [1.15,13.6], compared with children ages two to four years. Families earning more than $100,000 annually were less likely to report school performance issues, p = .005, OR = .27, 95% CI [.11-.67] compared with those who earned less than $50,000 per year.

Characteristics influencing the improvement of behavioral issues following participation in the intervention are shown in Table 4. Children who were better able to communicate about the illness following the intervention were reported to have improvement in sleep behaviors, p = .038, OR = 14.6, 95% CI [1.16,185], feelings of security at home, p = .013, OR = 18.33, 95% CI [1.84,182], and reduced feelings of anxiety/nervousness, p < .001, OR = 12.94, 95% CI [3.14,53.4]. When compared to families who participated in the intervention within three months of diagnosis, families who participated in the intervention more than three months following the diagnosis were less likely to report improvement with a child’s difficulty interacting with schoolmates, p = .014, OR = 12, 95% CI [.02,.65], and improvement in the relationship with the ill parent, p = .021, OR = 10, 95% CI [.01,.70]. Families were less likely to report that girls had improvement in sleep behaviors, p = .028, OR = 16, 95% CI [.03,.82], or anxiety, p = .012, OR = 16, 95% CI [.04,.67]. Improvement in difficulty interacting with schoolmates was less likely if the father was diagnosed with cancer, p = .043, OR = 18, 95% CI [.03,.95].

Discussion

The goal of this study was to identify predictors of various child outcomes following a psychosocial intervention for families experiencing parental cancer. These findings can guide the refinement of child life interventions used with this population as well as inform the design of future research studies, interventions, and child life programs. This study demonstrated that parents with cancer report that their children show improved psychological outcomes when participating in a child life intervention designed to address their worries and feelings. Because parents with cancer report that one of their biggest concerns is the well-being of their young children (Park et al., 2016), these results have the potential to also improve the psychological outcomes for parents.

Our study yielded several findings that warrant further investigation. Relationships were found among the amount of time between parental diagnosis and seeking services and specific child outcomes (interactions with schoolmates, relationships between children and their ill parent). Parents who received services for their child within three months of their initial diagnosis were more likely to see improvements in child outcomes. While previous research examines the amount of time since parental diagnosis (Dalton et al., 2019; Gazendam-Donofrio et al., 2007, 2009) as a variable related to parental distress, more studies are needed to explore how the amount of time since a parent’s diagnosis impacts a child’s response to interventions.

Additional relationships were found between financial difficulties and several intervention outcomes. These results are supported by interviews with adolescents who expressed concerns about the impact of parental cancer on their families’ financial circumstances (Phillips, 2015). Children in our sample were reported to have more difficulty with the ill parent relationship if the father had cancer and more likely to feel insecure at home if the mother had cancer. These findings support previous findings showing children had more difficulty in their relationship and communication when the ill parent was the father (Thastum et al., 2009; Visser et al., 2005). However, more than 60% of children were reported to have difficulty communicating about the cancer regardless of which parent was ill. More research is needed with larger samples of fathers with cancer to explore these correlations.

Our findings demonstrate that improvements in the ability of the child to communicate about their parent’s illness was associated with improvement in child’s ability to sleep and feel secure at home as well as a decrease in their feelings of anxiety. This is supported by previous studies that found parent-child communication to be a consistent variable related to child’s functioning when a parent had cancer (Dalton et al., 2019; Lewis, 2011; Stefanou et al., 2020; Visser et al., 2004, 2006)

Existing qualitative literature reports on the robust post-traumatic growth experienced by African American adolescents coping with a parents’ cancer diagnosis (Kissil et al., 2010). However, few researchers have explored racial differences in intervention studies among this population. Our results found families of color (22.4% of our sample) were less likely to report issues with poor school performance, feeling insecure at home, and feelings of anxiety or nervousness. Future studies with larger and more diverse sample sizes are needed to confirm these findings. Moreover, more research is needed to identify potential barriers to participation in these types of psychosocial services among families of color, including examining differential responses to culturally adapted psychosocial interventions for children and families experiencing parental cancer (Davey et al., 2005; McKinney et al., 2018).

Limitations

The study design was exploratory and conclusions regarding causality between intervention participation and observed outcomes cannot be drawn from these results. Interpretation of these findings may also be limited by the fact that those who responded to the survey may have been demographically dissimilar than families who did not respond. The survey itself was developed in the community setting by the agency staff and an independent research firm to elucidate specific information not previously described in standardized measures. Outcomes were reported by only one parent and only on one occasion at varying time points within six months post-intervention. Therefore, misclassification of outcomes through recall bias may have resulted from variance in time survey was administered post-intervention. Behavioral issues reported were only parent observations or perceptions of distress in their children. Moreover, it was not possible to consider potentially informative variables such as stage of cancer, precise timing of survey response following the intervention, or the exact number of intervention sessions attended because of limitations of the data set provided.

Future research should include use of standardized measures collected at baseline and post intervention as well as child reported measures to account for inconsistencies with parent perceptions of distress and child outcomes.

Implications for Psychosocial Oncology and Child Life

This study demonstrated that parents with cancer report their children show improved psychological outcomes when participating in a psychosocial intervention provided by child life specialists. Because parents with cancer report that one of their biggest concerns is the well-being of their young children, these results also have the potential to improve the psychological outcomes for parents. Results indicate that providing families access to services within three months of initial diagnosis is important. Moreover, results indicate that families benefit from interventions focused on ways to communicate more openly about the illness. Child life specialists can use these findings to target appropriate interventions for families at most risk of negative outcomes due to parental illness. Given the tremendous number of children impacted by parental cancer and the long-lasting impact of their distress, additional studies of interventions using rigorous design, control groups, and standardized measures is warranted. In addition, it would be important for child life specialists to engage with underserved populations to assess reasons for lack of interest or participation to culturally adapt the intervention to better serve multiple racial and ethnic groups.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data Sharing

Research data are not shared.