There has been significant growth in the child life profession since its inception in the 1920s and formalization in 1982 (Turner & Brown, 2016). There were approximately 200 members in the first year of the Child Life Council (now known as the Association of Child Life Professionals [ACLP]) in 1982 (ACLP, 2024). Today there are over 6,600 Certified Child Life Specialists (CCLS) worldwide according to the Child Life Certification Commission (CLCC, 2024a). This growth has helped to spur greater standardization of child life professional entry requirements, namely more specific academic coursework and increased clinical internship training hour expectations for emerging child life professionals (CLCC, 2024a). While the evidence base for clinical child life service provision and academic training has strengthened (Boles et al., 2021), much less is known about the child life internship process and potential opportunities for optimization.

To become a CCLS, an individual must sit for and successfully pass the Child Life Professional Certification Examination (CLCC, 2024b). To be exam eligible, applicants must complete 1) a minimum of a bachelor’s degree, 2) 10 specific academic courses (child development, loss and bereavement, play, research, family systems, child life course taught by a CCLS, three electives), and 3) a 600-hour internship (CLCC, 2024b). The internship must be completed under the supervision of a CCLS with at least 4,000 hours of paid clinical experience as a CCLS and provide opportunities to demonstrate competence in each element of the exam content outline (CLCC, 2024b). With these criteria in place, the availability of internships are often limited to hospital-based child life programs with supervisors who have the requisite amounts of clinical experience and willingness to supervise interns.

Over the years, child life internships have been viewed as a narrow tunnel aspiring professionals must pass through to enter the profession, while others have plainly referred to internships as the gatekeepers to the profession (Boles et al., 2024; Johnson & Read, 2024; Sisk et al., 2023). This has perhaps become even more of a reality in recent years as CCLSs have reported increased burnout and job turnover and a “staffing crisis” in the profession (ACLP, 2023; Burns-Nader et al., 2024; Jenkins et al., 2023). Such variables have decreased the number of staff available, eligible, and willing to supervise interns, thus decreasing the number of child life clinical internship positions available each cycle (ACLP, 2023; Heering, 2022). In fact, a recent study reported that only 54.4% of the study participants obtained a child life internship (Boles et al., 2025).

Not only is it difficult for students to locate and obtain internships, but the process of applying and competing amongst peers for these limited positions takes a toll on the well-being of aspiring professionals (Boles et al., 2024). Historically, the child life internship process is a competitive one in which aspiring professionals apply to a number of hospitals and use their essay writing and interview skills to demonstrate their internship readiness (ACLP, 2024a), often competing among 100 or more applicants per site. The Internship Readiness Common Application, released by the Association of Child Life Professionals in Fall 2023, asks applicants to list up to six experiences with children, with at least one being an experience with children in the healthcare setting (ACLP, 2024b). However, each clinical site may assess applicants using their own individualized standards or preferences that are often unknown to the applicant (Sisk et al., 2023). For example, one site may prefer an intern to have completed a traditional, in-hospital child life practicum while another may instead prefer a range of pre-internship experiences in varied settings. The current child life internship application process often leaves aspiring professionals experiencing exhaustion related to the emotional and cognitive loads of navigating the lack of information about the process and the increased financial costs of applying and relocating should they be successful (Boles et al., 2024).

There is developing evidence that among aspiring professionals, there are predictors of success in obtaining internships (Boles et al., 2025), including some graduate level training, completion of a child life practicum in a healthcare setting, and a CCLS faculty member available for advising and mentorship throughout the application process (Boles et al., 2025; Sisk et al., 2023). Previous research has also highlighted that financial costs and the need to relocate for a full-time internship are barriers that applicants may experience, with such socioeconomic barriers disproportionately affecting aspiring professionals of color, those who are raising families, or balancing employment while pursuing a child life career (Boles et al., 2024; Gourley et al., 2023; Sisk et al., 2023). Such findings suggest that the internship process may be a factor constraining more diverse representation in the child life profession.

For internship coordinators, the number of applications received has been found to influence how and to what extent applications are reviewed (Sisk et al., 2023). In a recent study, internship coordinators noted that fewer applicants would allow them to take more time to review applications and that increased numbers of applicants often lowers the percentage of applicants they are able to invite to interviews (Sisk et al., 2023). Furthermore, the study found that it was common for internship positions to go unfilled if internship sites did not find an applicant who they deemed to be appropriate for the internship position (Sisk et al., 2023). In a staffing crisis in which programs are experiencing the inability to fill open positions, there is a need to fill all internship positions in hopes of training individuals to enter the profession and occupy child life jobs.

Many medical and allied health professions use a matching program or process to place aspiring professionals in their clinical training programs, including physicians (Kortz et al., 2021), dieticians (Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics [ACEND], 2023), psychiatrists (Williamson et al., 2022), psychologists (Association of Psychology Postdoctoral and Internship Centers, 2024), and pharmacists (American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, 2024). Matching programs serve to match applicants and clinical training programs based on bi-directional ranking algorithms. Typically, applicants rank clinical training sites and training sites rank applicants, with an objective, statistical test then determining which applicant goes to which site. According to the National Resident Matching Program (2024), a matching system:

encourages applicants and training programs to honestly identify where and who they want to train; offers unbiased space and ample time for applicants and programs to strategically consider their training options; and maintains advanced, secure technology for the confidential ranking of preferences. Match outcomes are accurate and the process stable because participants control who and how their preferences for training are ranked (p.1).

Evidence to date demonstrates that matching programs 1) increase the number of positions filled (ACEND, 2023; Williamson et al., 2022), 2) provide crucial data on how to better prepare candidates (Kortz et al., 2021), and 3) favor student preference, thereby giving aspiring professionals a sense of control in the process (Maaz, 2020).

The outcomes achieved from these programs in healthcare professions closely resonate with the current challenges seen in child life clinical training. However, evidence is needed to actively explore the feasibility and utility of a student matching system for child life internship applicants, clinical internship committees, and academics. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore the implementation of a regional child life internship matching pilot program from the perspectives of participating students, clinical internship coordinators, internship committee members, and child life academicians. The following research questions guided this study:

-

How do child life students, internship coordinators, internship committee members, and academic coordinators rate their satisfaction with the regional matching system?

-

How do child life students, internship coordinators, and academic coordinators describe their experiences with the regional matching system?

-

How do the experiences of child life students, internship coordinators, internship committee members, and academic coordinators help explain satisfaction levels with the regional matching system?

Method

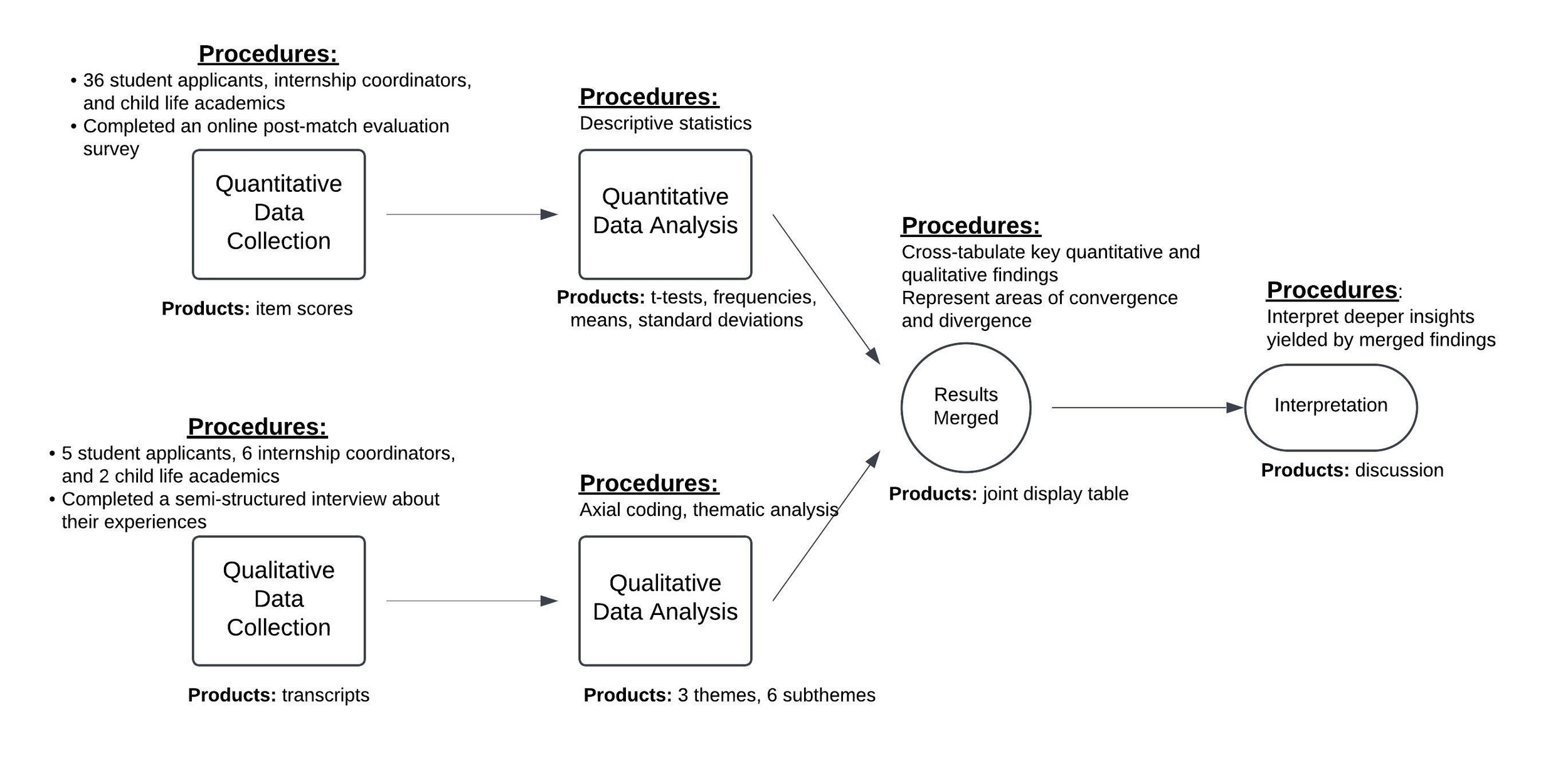

To address the research questions in greater depth, a convergent, parallel mixed-methods study was employed; therefore, quantitative and qualitative data collection methods were conducted alongside one another (Creswell & Clark, 2018). The quantitative arm gathered data on outcomes related to satisfaction, likelihood to participate in a matching program again, and impact on time commitment via electronic survey, and semi-structured interviews centered on participant experiences with the matching program comprised the qualitative arm. In addition to exploring the insights yielded by both sets of methods, convergent mixed-methods research includes an additional integration of all results into a final integrated analysis (See Figure 1).

Child Life Internship Matching Program Pilot

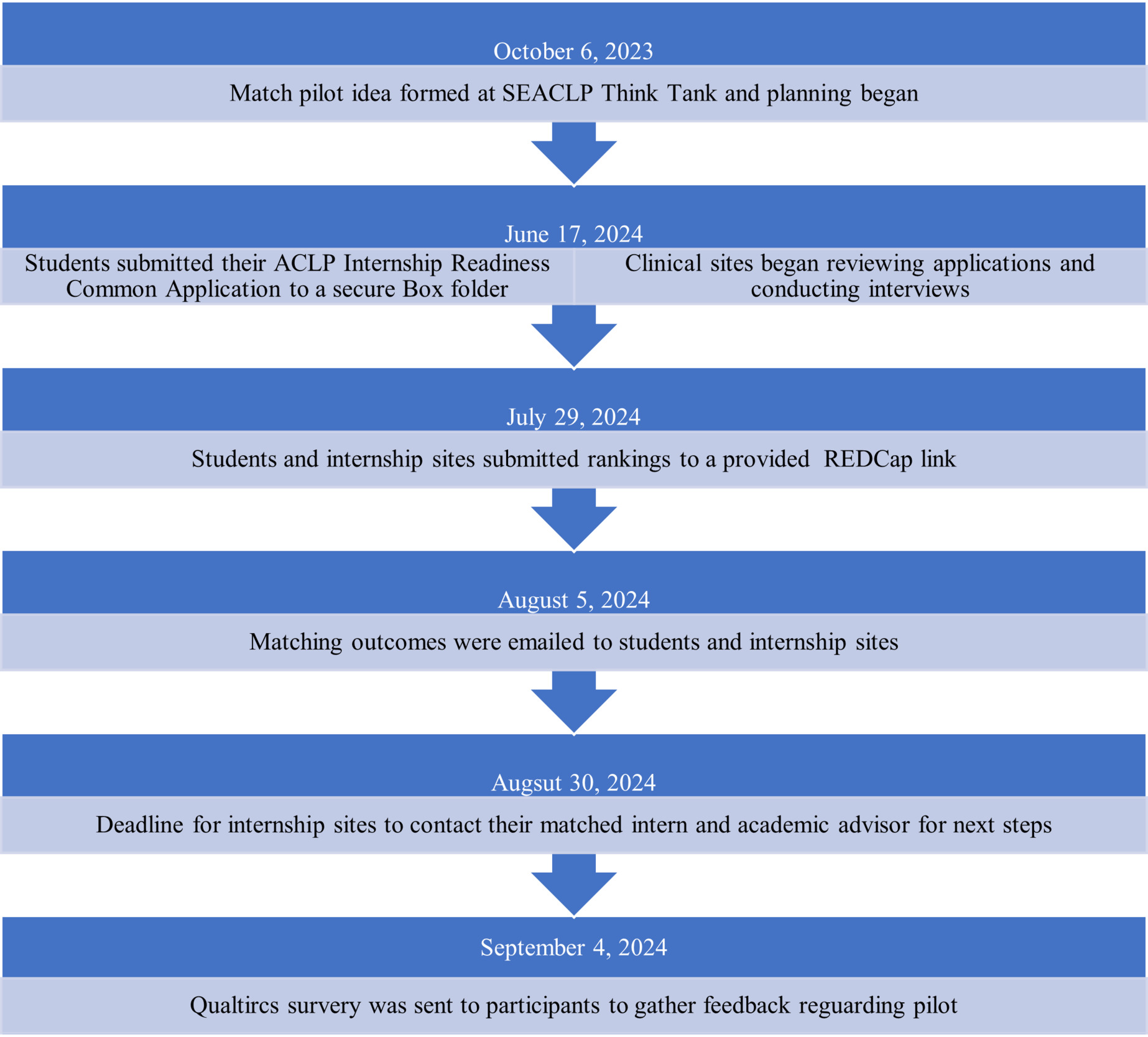

The Southeastern Association of Child Life Professionals (SEACLP) is a regional child life organization serving child life professionals and students in Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee. Each year, SEACLP hosts a Think Tank uniting academic and student clinical (practicum and internship) leaders in a day of networking and problem-solving issues related to student training. During the 2023 Think Tank, attendees voiced an interest and commitment of time and resources into piloting an internship matching program and tasked the SEACLP Academic and Clinical Working Group with leading the initiative. The Academic and Clinical Working Group consisted of three academic leaders, three internship coordinators, a chair, and a board liaison; the group’s mission was to work on initiatives related to increasing collaboration between academic and clinical experiences. Over an 8-month period, the Academic and Clinical Working Group of SEACLP developed, planned, communicated, and implemented the pilot initiative. The pilot was facilitated by these volunteers and required no monetary or additional personnel resources.

The goal of the pilot was to examine the feasibility of a regional child life internship matching program and explore the benefits for the key stakeholders: students, internship, coordinators, internship committee members, and academic coordinators. After developing focal documents (e.g., goals, inclusion criteria, procedure, and timeline), the working group contacted all academic and clinical programs who met the inclusion criteria (offered a child life major/concentration or offered a child life internship) to share this information and provide potential participants an opportunity to ask questions, note concerns, and provide feedback. Clinical and academic sites completed an electronic survey via Qualtrics to declare their intent to participate and report on pre-implementation data (e.g., type of hospital or academic program, number of child life specialists, and hours typically spent reviewing applications).

To be eligible to apply to the matching program, a student had to be degree-seeking and actively enrolled in one of the academic programs of the SEACLP region that offered a child life major/concentration. To participate, each student had to submit a completed application which included the Internship Readiness Common Application, an unofficial transcript, and a CLCC eligibility report. The pilot was offered prior to the ACLP general application dates to provide those students who were not matched the opportunity to apply to other internship positions. Prior to the pilot, representatives from participating sites attended an information session led by the Academic and Clinical Working Group and then returned to their programs to share the information with team members or students. Internship sites also established affiliation agreements with academic programs if agreements did not already exist.

In June 2024, participating students sent one email with their completed Internship Readiness Common Application (which included the fillable pdf document, a copy of their eligibility assessment, and unofficial transcripts) to a SEACLP email account created solely for the pilot. Two representatives from the Academic and Clinical Working Group reviewed all applications. Applications that did not meet eligibility requirements were returned to the student. Eligible applications were uploaded to a secure Box folder, and internship site coordinators were provided a link to view and download all applications. Internship sites had a total of six weeks to review applications and conduct interviews at their program’s discretion. All interviews were conducted through phone, Zoom, or a combination of both; no in-person interviews were offered.

On the specified “ranking day” (six weeks after applications were submitted), all student participants and clinical internship coordinators received an email from the Academic and Clinical Working Group with an individualized REDCap link and instructions to submit their numerical rankings. Students ranked the six participating sites from most to least preferred; clinical coordinators ranked all 31 student participants in the same manner. Sites and students did not provide any additional information about or explanation of their rankings – only the rankings they assigned to each. On the specified “match day,” the Academic and Clinical Working Group emailed each student and internship site with notification of their match outcomes. To protect confidentiality, students and sites were only notified of the specific site or student with whom they had been matched, as is standard in other professional matching programs. Students who were not matched were also notified and were encouraged to apply for the Spring 2025 ACLP national internship cycle and request feedback from internship sites to improve their application. See Figure 2 for the timeline of the matching pilot.

Matching Algorithm

This matching program was designed to assign candidates to an internship location while considering both the internship site’s preference and candidate’s site preference. Using a ranking system, a statistical approach was developed using a chi squared framework. The formula for a Chi Square is Σ

Chi squared was chosen due to its nature as a “goodness of fit” test, meaning that it first expresses the difference between observed values and expected values and next compares how well the observed value fits the expected value. Using this idea, a theoretical value of “0” was assigned to represent a “perfect match,” or a candidate that an internship location has determined is their first preference and that candidate has also favored the site as their first choice. A numerical framework needed to be designed to represent the idea that a perfect candidate scores a “0” or perfectly matches the expected outcome.

The system created assigned the internship sites ranking of a candidate as a whole number: 1 for rank 1, 2 for rank 2, and so on. Meanwhile a candidate’s preference in internship location was assigned a number in the tenths place: rank 1 as .1, rank 2 as .2, etc. This results in scores of 1.1, 1.3, 2.2, etc. This was done for several reasons. First, assigning ranking scores allows the raw rating score to be visually viewed. A score of 2.3 would correspond with a site ranking of 2 and a candidate ranking of 3. This allowed the user of the system to visually identify the matching score to the corresponding rankings.

Second, the site’s ranking was assigned a whole number so it would contribute more to a match score and a candidate’s preference was assigned a lower value to resolve ties in scoring. For example, if two sites both ranked a candidate as their first choice that would result in the same match score, but because the candidate’s ranking was included that match score would change depending on the candidate’s preference. The lower value assigned to the candidate’s ranking ensured that a candidate’s preference could not supersede the choice of the internship site. The system allowed a score to be created for every site and candidate combination, and each score to be unique if a rank was given by each party.

The described approach treats the expected value as the theoretical perfect candidate, or a ranking of 1.1. When the observed score is plugged into a chi squared formula, a match score is derived. Entering a raw ranked score results in a unique value for each candidate’s matching score. As an example, a raw matching score of 3.2 would represent an internship site ranking a candidate as their third choice and the candidate ranked the site as their second choice. This value would then be calculated in the formula as 4.009. This score is the overall matching score. Due to the nature of the ranking system, no matching score would be the same across sites or candidates, producing scores where there are no ties for any one open spot. Additionally, if a candidate received a rank score of 1.1 the formula would produce a result of 0, representing a perfect match score. This method ensured that each internship site got the best matching student for their program and that a student’s preference of site is taken into consideration. The program thus retains choice and preference for both parties involved.

Procedures

Data for this study were collected as part of a larger longitudinal study that received exempt-level approval from an Institution Review Board of a large public university in the Southeast (Protocol 24-06-7732). Individuals who participated in the pilot (i.e., students, internship coordinators, internship committee members, and academic coordinators) received an email that provided a summary and link to the study. Those interested in participating visited the link where they received additional information and provided informed consent electronically.

Data Collection

Throughout the study, quantitative and qualitative data were collected simultaneously. Once participants provided electronic consent, they completed an electronic survey via Qualtrics to gather quantitative data. The survey was created by the research team members for the purpose of this study. First, the survey collected information about participant background including race, ethnicity, gender, age, and role (e.g., student and academic coordinator), as well as descriptions of programs (e.g., type of academic program, type of hospital, and number of child life specialists on team). The survey then asked participants to share their satisfaction level on a scale from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 5 (very satisfied) on aspects of the matching program including procedures, communication, outcomes, ease of application, and likelihood to participate in a matching program again on a scale from 1(not likely at all) to 5 (very likely). Those individuals who had participated in the internship application prior to the pilot were asked to compare the matching program to the general internship process on commitment of time, commitment of resources, and emotional load using a scale from 1 (not better at all) to 5 (much better). Internship coordinators were also asked to share information about time involved in reviewing applications and completing interviews. Information about student pre-internship experiences and coursework was extracted from their Internship Readiness Common Application.

After completing the survey, participants could opt into an additional interview to discuss their experiences and feedback in more detail (see Appendix for interview guides). Each interview was conducted via Zoom teleconferencing software by a trained graduate student who was not directly involved in the pilot to minimize potential response bias. Each interview was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Analyses

Initially, quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed separately, and then findings were interpreted together to see where findings converged or diverged from one another (Creswell & Clark, 2018).

Quantitative Analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 29 was used to examine the quantitative data. Frequencies and percentages were used for nominal data such as race, ethnicity, type of hospital, and type of university. Means and standard deviations were used to provide averages of ordinal variables including age, number of hours reviewing applications, and number of pre-internship hours. Medians were also used to explore Likert scores on the measures of importance of participating in the pilot, satisfaction, comparison to the general application process, and likelihood to participate in a matching program again. Paired samples t-test were used to compare reported hours reviewing application from the previous internship cycle to that of the matching program.

Qualitative Analysis

Interview transcripts were coded using a line-by-line, inductive coding approach developed by Boles and colleagues (2017) and drawn from the psychological phenomenological tradition (Moustakas, 1994). Each transcript was separately coded by two members of the research team to ensure multiple perspectives were represented. All codes generated by the different team members were combined into a master coding document, in which repeated or overlapping codes were combined into larger categories. Transcripts were then re-reviewed to ensure that categories were an accurate and complete reflection of participants’ responses. Next, categories were considered in their relationships to one another and the transcripts, leading to the development of themes. Transcripts were again reviewed to ensure themes were as grounded in the data as possible.

Integrated Analysis

As part of the convergent mixed methods design, after quantitative and qualitative analysis have been completed separately, they are then explored together to see where they align or diverge (Creswell & Clark, 2018). A joint display table was used to summarize the convergence of quantitative and qualitative data (See Figure 3).

Reflexivity Statement

This study was designed and conducted primarily by three CCLSs with over 50 total years of clinical experience across multiple states, institutions, populations, and settings. Additionally, those authors either hold or are in the process of completing a doctoral degree in fields such as human development and family studies, educational psychology, and educational leadership; together they have participated in the academic preparation of aspiring child life professionals since 2010. Additional members of the study team brought 23 more years of clinical experience to the project from two other institutions and patient populations. Finally, external to the child life field apart from this project, but with a history of collaborating with healthcare teams, one author contributed five years of statistical consulting expertise to the team.

Results

Quantitative Results

Pilot Program Participants

Eight child life academic programs and all seven clinical internship sites in the region met the inclusion criteria and were invited to participate in the internship matching pilot. All academic programs chose to participate; however, two programs did not have eligible applicants at the time of the internship pilot program. Six out of the seven internship sites chose to participate, with one program opting out due to staffing changes and inability to offer a child life internship for the Spring 2025 cycle.

Overall, the academic programs were largely housed in public universities, and the majority offered concentrations over majors in child life at both the undergraduate and graduate level. The participating clinical sites were primarily freestanding children’s hospitals that employed seven or more CCLSs (See Table 1 below). Across the six clinical internship sites, there were 10 internship positions available.

Thirty-five individual students submitted applications to participate in the matching pilot. Of those, two applicants did not meet the criteria for eligibility and two additional students withdrew, leaving 31 students who participated in the matching pilot. With 10 available internship positions, the 31 applicants had a 32.3% chance of being successfully matched. The majority of the pilot participants were undergraduates (n = 21, 67.7%), had the 10 courses required for eligibility completed at the time of application (n = 17, 54.8%), listed six experiences with children on their application (n = 25, 80.7%), and had a child life practicum completed at the time of application (n = 26, 83.9%;See Table 1).

Motivation for Participating

Prior to participating in the pilot, academic and clinical sites were asked how important it was to trial a pilot for internship placement on a scale from 0 (not at all important) to 10 (most important). Overall, academic and clinical programs felt it was very important to trial a pilot, with a median score of 9.50 (IQR = 3.5).

Match Outcomes

Ten student applicants were successfully matched with a participating clinical internship site at the conclusion of this pilot program. A slight majority (n = 6, 60%) of these were master’s prepared and most had completed a traditional child life practicum with more than 100 hours of this practicum completed prior to internship application (n = 8, 80%). Two students were completing a child life practicum during the pilot program. Additionally, eight of the 10 (80%) included six experiences with children on their Internship Readiness Common Application. All individuals who were matched were from an academic program with a full-time CCLS on faculty and had at least 100 hours of experience with children in the healthcare setting (See Table 2).

Study Participants

Two weeks after completion of the internship match pilot program, all participating students, internship coordinators, internship committee members, and academic coordinators were invited to participate in an online survey and optional interview to evaluate the match program. A total of 36 individuals chose to participate in this study, including 16 (44.4%) students, nine (25.0%) internship committee members, six (16.7%) clinical coordinators, and five (13.9%) academic coordinators. Participant demographics can be seen in Table 3.

Participants ranged in age from 20 to 58 years, with a mean age of 29.4 (SD = 9.7). Of those that reported gender and race, all were female and most were White. Such findings regarding race and gender are not surprising as the child life profession is predominately White and female (Ferrer, 2021). There were slightly more undergraduate students (n = 9, 56.3%) participating in the study, with most student participants reporting this was their first time applying to internships (n = 14, 87.5%). Seven of the 16 students who participated in the survey were matched to an internship site (41.2%). Clinical participants (internship coordinators and committee members) were mostly from freestanding children’s hospitals that employed at least 10 CCLSs. Academic participants were from programs that all had a CCLS faculty member and mostly offered child life coursework in a major or concentration.

Matching Program Evaluation

Participants were asked to rate on a scale from 1 (not likely at all) to 5 (very likely) how likely they would participate in the pilot again, and overall, they appeared to be very likely to participate again (mdn = 5.0, IQR = 1). When asked about their satisfaction on a scale from 1 (extremely dissatisfied) to 5 (extremely satisfied), participants reported they were extremely satisfied with the procedures (mdn = 5.0, IQR = 1), outcome (mdn = 5.0, IQR = 1), and ease of application (mdn = 5.0, IQR = 2) and were satisfied with the communication about the pilot (mdn = 4.0, IQR = 2.75).

Clinical and academic participants, as well as student participants who had previously applied to internships, were asked to compare the commitment of time, resources, and emotional load of the pilot to the national child life internship application process on a scale from 1 (much worse) to 5 (much better). Participants felt the pilot was a better commitment of time (mdn = 5.0, IQR = 1), resources (mdn = 4.0, IQR = 2), and emotional load (mdn = 3.5, IQR = 2) compared to the general application process. See Table 4 below for a summary of scores of the individual groups across these variables.

Internship coordinators were extremely satisfied (mdn = 5.0, IQR = 1) with the time required of the pilot (see Table 4). In the national application process prior to the pilot, the internship sites who participated in the survey received between 65 to 250 applications (M = 138.7, SD = 70.6) and spent between 25 to 140 hours reviewing internship applications (M= 80, SD = 46.4). During the pilot, these internship sites reported spending an average of 22.4 (SD = 19.3) hours reviewing internship applications. Compared to the general application process, there was a significant decrease in the amount of time sites spent reviewing applications for the pilot (t (4) = 3.1, p < 0.01).

Qualitative Results

A total of five students, six child life internship coordinators, and two child life academics chose to participate in an additional semi-structured interview about their experiences in the regional internship match pilot program. Of the five participating students, four were graduate students and one was an undergraduate. All five were successfully matched in the pilot program. Both academic participants were employed in undergraduate child life programs; only one of these had a student successfully match in the pilot program.

To contextualize participant interview responses, the open-ended responses from the pre-participation survey were reviewed. In these, participants spoke to a range of motivations for participating in the regional match pilot program. Several coordinators and academics discussed a desire to take action and try something new in the face of a system currently recognized to be “challenging,” with an ultimate aim of creating positive growth and outcomes for aspiring child life professionals. Additionally, two clinical coordinators mentioned motivation to invest in local students and local placements as a means of acquiring new local employees to mitigate the impacts of staffing vacancies. Finally, students, coordinators, and academics reported belief in the potential depth of impact such a pilot program could have on both local and national levels.

Post-match, participant perceptions and insights clustered around three themes: 1) “saved me stress and simplified a very overwhelming process,” 2) “a great way to alleviate the burden on students and your team,” and 3) “a wonderful opportunity for students and a collective group of professionals.”

“Saved Me Stress and Simplified a Very Overwhelming Process”

The five student interview participants shared a range of perspectives on the internship match pilot, with all expressing gratitude for the opportunity and describing it as a positive experience. Students reported relying on a variety of support systems throughout the process, including professors, family, peers, practicum supervisors, alumni, current interns, and online resources. Key aspects of the pilot that students appreciated included reduced stress, improved odds of placement, a streamlined timeline, opportunities to practice interviewing, and the overall simplification of the process. However, participants noted that communication from clinical sites about the interview process and the timing of updates could have been improved to better support students during the match.

Perceived benefits of pilot program. The students identified numerous perceived benefits of the pilot program. They noted experiencing less stress, which they attributed to the smaller program size, reduced competition, and a clearer process. Three students specifically mentioned that the pilot program alleviated stress, with one student comparing the traditional process to “trying to solve riddles.” Participants also appreciated the clear communication from SEACLP and the tighter timeline, which limited the time available to dwell on outcomes. Beyond stress reduction, students highlighted the potential mental health benefits of being placed closer to home. They noted that staying near family allowed for weekend visits and eliminated the need to adjust to a new geographic location, contributing to their overall well-being. Additionally, students recognized better odds of success and viewed the pilot as a valuable opportunity to gain skills and experience, even if they were not matched. One student shared, “It felt like a safe place to apply.” They appreciated that the process mirrored the national cycle, requiring no additional effort, and did not affect their ability to participate in the national cycle if needed. Finally, students emphasized that the pilot program simplified the overall experience and provided them with more interview opportunities than they had received during the national cycle.

Perceived areas for improvement. Students identified several areas for improvement in future child life match programs. Students emphasized the importance of strong and consistent communication with clinical sites. While this was seen as an improvement compared to the national cycle, inconsistencies in communication about interview structures and progress impacted students’ ability to navigate the ranking process effectively. Additionally, students highlighted the lack of standardization across hospital sites regarding communication and interview procedures as a source of stress. They expressed a desire for clearer guidelines and transparency about interview processes for each site. Finally, despite the many perceived benefits of the pilot program, students noted the significant stress associated with the internship process in general. They pointed to the uncertainties surrounding decision day and the varied processes used by individual hospitals as contributing factors to this stress.

“A Great Way to Alleviate the Burden on Students and Your Team”

The six clinical coordinator semi-structured interview participants frequently referred to the match program from this standpoint, describing how they felt the program lessened logistical, practical, and emotional stressors they typically experience during the traditional internship application process. Participants reported they primarily retained their same application review and interview processes; however, with fewer candidates that they also perceived as high-quality applicants, less time was required of clinical staff to complete the match program. They identified several benefits associated with the regional internship match pilot program as well as opportunities for future improvement, stating excitement about and plans to continue participating in the internship match process.

Perceived benefits of pilot program. In terms of practicality, clinical internship coordinators found that the centralized Box folder application repository allowed for quick and complete application access, which saved hours of time organizing and distributing files. These time savings were easily redistributed; as one coordinator shared, “I was able to spend more time being intentional in the application review process…and the majority of our people were able to do [application reviews] within their work hours for this cycle, and that definitely is not always the case with the [national] process.”

Coordinators also verbalized appreciation for being able to spend more time reviewing applications for and conducting interviews with students from their local region. In addition to feeling more personally connected to local students, coordinators felt this investment was more likely to directly benefit their clinical programs. While one coordinator shared her facility’s human resources preference to hire local candidates, another echoed a similar sentiment:

We know that we would prefer an intern to be local, just because we would hope and think that they may stay as a practicing child life specialist in the region. So that’s why we were really excited for the match program because it’s including people that are in [our region]. And it’s really helping those students maybe get internships closer to home which can help with any financial burdens that they may have or just mental health in general. It could just be helpful being closer to home just for that transitioning from student to professional aspect.

Overall, coordinators reported appreciation for the time and energy savings they experienced during the pilot program, as well as the region’s focus on improving experiences for local students and clinical programs.

Perceived areas for improvement. Clinical coordinators also identified opportunities for improvement based on their experiences. Some articulated a need for more frequent communication from the working group running the matching program and suggested creating a brief presentation about the structure of the program for sharing with their clinical team members. They also raised insightful questions about the potential benefits or risks of standardizing the interview process across participating clinical sites, stating interest in learning more about each site’s review and interview process for their own learning and consideration. As a coordinator shared:

We would also just love to hear what other hospitals did to rank all of the students. I know that some hospitals don’t always want to disclose that, but we’re always wanting to make our internship process as good as it can be.

Finally, sites requested more information or guidance on if, when, or how to send decline emails during the interview process and how this might impact the ranking algorithm.

“A Wonderful Opportunity for Students and a Collective Group of Professionals”

The two child life academics described the internship pilot as a significant opportunity for both students and the child life profession, emphasizing its innovative contribution to the field. Participants reflected on the regional match pilot, noting that its preparation requirements were consistent with the national internship cycle, while also providing students with valuable practice and skill development for their future careers. One key distinction highlighted was the additional support and preparation students required due to the tight timeline of the match process and the ranking system utilized. Participants identified numerous benefits of the pilot, as well as areas for potential improvement. They expressed optimism about the future of the regional match, envisioning its potential to strengthen clinical and academic partnerships within the field.

Perceived benefits of pilot program. Regarding student experiences, child life academics highlighted that the pilot program provided students with greater balance, confidence, and a sense of control. They emphasized that the program empowered students by giving them a voice in the process, fostering a sense of security, and enhancing their overall learning experience. One noted, “… the opportunity to rank the hospitals was also really a significant thing for them because they really felt like … they had a voice in it.” The requirement to complete a common application and interview with multiple clinical sites allowed students to refine their interview skills and articulate their experiences effectively. These skills, participants noted, would be advantageous for students who were not matched in the pilot and planned to apply during the national cycle.

Additionally, the child life academics expressed a preference for the pilot program over the national cycle, citing improved clarity about placement odds, process expectations, and communication with clinical sites. They also noted that the odds of placement through the pilot program were higher than those in the national cycle, further supporting its value for students. Another stated:

You know, only 10 out of approximately 30 students were matched. And so it’s only a third. But still, I think, a one in three ratio is a lot better than what they currently have from a national perspective.

In terms of the participating child life academics, they shared that the support they provided to the student was similar to what they typically extend in the national cycle. The participants reviewed the common application that included the students’ experiences; knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSA); and talked about their experiences in the pilot with them. Participants also noted that they informed the students about the match pilot and left it up to them if they wanted to participate.

Perceived areas for improvement. Participants identified areas for improvement related to the logistics of the program. While the condensed timeline was seen as more manageable for students, it posed challenges for academicians, particularly when negotiating graduate deadlines for students who were not matched. Participants also suggested that increasing flexibility in eligibility requirements could expand access to the match, specifically recommending consideration for recently graduated students. Consistent with feedback from students, although improved communication was highlighted as a strength of the pilot, participants noted that establishing clear and defined timeframes for hospital communication would further benefit students and enhance the overall process.

Integrated Results

In bringing the quantitative and qualitative results of this study together, several insights can be gained (as depicted in Table 5 below). First, it appears from the perspectives of participants that the match program helped to optimize the amount of time each spent participating in the internship application and selection process. Additionally, their high satisfaction ratings could potentially be explained by the qualitative finding depicting an experience with lesser commitments of time, thought, and emotional energy than they felt were required in the national internship cycle. All participants spoke to the value of communication throughout the matching program pilot, identifying communication tactics as both a strength and an area for improvement in future iterations. Finally, these findings together led to the last integrated result, that participating child life students, internship coordinators, and academics reported resounding interest in continuing the internship match program pilot in the future.

Discussion

This study examined the outcomes of and participant experiences with a regional child life internship matching program piloted by SEACLP. Overall, students, internship coordinators, internship committee members, and academics were very satisfied with the internship matching program and stated they would be willing to participate again. The internship matching program had substantial perceived and actual benefits for all participating parties, including reduced time commitment and emotional and cognitive load throughout the process. Internship coordinators and students particularly noted the reduced time burden, highlighting the efficiency of the system in simplifying administrative tasks and coordination efforts.

Matching programs in other health professions have been found to increase the number of positions filled (ACEND, 2023; Williamson et al., 2022); likewise, in this pilot program, all 10 internship positions were successfully filled with internship coordinators stating satisfaction with the outcomes. This is an optimistic finding, as a previous study found that it is typical for child life internship positions to go unfilled (Sisk et al., 2023). The successful placement of more students into internship sites is a vital step toward addressing the current staffing crisis. By increasing the number of qualified professionals ready to enter the workforce, the regional internship match program has the potential to support the sustainability and growth of child life services across healthcare settings, and particularly within the target region.

One of the most significant outcomes observed in this pilot program was the reduced emotional distress participants associated with the internship application process. Prior work has found the internship process to be associated with emotional exhaustion (as a subscale of the burnout inventory) due to the lack of procedures being streamlined across programs and concern regarding meeting implicit expectations (Boles et al., 2024; Reeves, 2019). The current study found that an internship matching program has the ability to address such burdens by reducing the emotional and cognitive load and increasing consistency and predictability in the application and interview process. The procedures for the SEACLP internship matching pilot were streamlined and shared with all involved parties before students applied, ensuring that all were sufficiently prepared and well-informed. Participants in this study appreciated the improved communication regarding the internship process but also indicated that there is still room for further refinement in communication. With the additional information and communication provided in the pilot program, students appeared to better recognize their own involvement in the process, giving them a sense of control which is a common benefit associated with matching programs in other professions (Maaz, 2020).

Internship coordinators and students perceived spending less time overall in the internship match pilot as compared to the national cycle. Prior studies have documented numerous student challenges related to time management during the internship application and selection process (Boles et al., 2024; Reeves, 2019). Additionally, research by Sisk and colleagues (2023) demonstrated that child life academics are dedicating additional time to support students who undergo multiple rounds of internship applications after not securing a position. The results of the present study suggest that students, clinical coordinators, and academics all view a regional internship match program as requiring less time and energy. The findings of this study offer valuable insights for future child life internship applicants, clinical coordinators, and academics, highlighting factors that increase the likelihood of attaining an internship. A key advantage of a matching program is that it equips child life academics with insights on how best to prepare aspiring professionals (Kortz et al., 2021). The current study adds to the growing body of literature by identifying the qualities most valued during the internship application process. Academics can utilize this information and that from Boles and colleagues (2025) to provide guidance into what internship sites are looking for in applicants.

Internship coordinators, child life academics, and students all shared that they would participate in an internship matching pilot again. Feedback from participants has been overwhelmingly positive, with many expressing a desire to engage with the program again. The internship match pilot program by SEACLP stands as a beneficial innovation in the field of child life education and practice. It appears to foster a more efficient, less burdensome internship matching process that benefits students, internship coordinators, internship committee members, and academics alike. The continued success of such initiatives may be essential for the ongoing development of the field and the effective support of the children and families served.

Limitations

Like any study, the current study has limitations that should be noted. One limitation is the small sample size which was in part due to limited number of eligible participants set by the criteria of the regional internship matching program. In addition, the participants were mostly White and all females. Although this was expected because the child life profession is predominately White and female (Ferrer, 2021), future studies should try to recruit a more diverse sample. A third limitation was the possibility of the self-selection bias because only students matched for an internship chose to participate in the interview portion of this study. The current study did try to recruit those who were not matched but those individuals did not choose to participate. Future studies should continue to include the perspective of those that were not matched. Also, this study only included students who were matriculating and degree-seeking from an academic institution with a child life major or concentration; therefore, the results may not generalize across other populations of aspiring professionals.

Implications

Members of the child life community have questioned the feasibility of a matching program for child life internships (Sisk et al., 2023). The current findings provide evidence that a regional internship matching program can be successful and beneficial. The child life profession should consider offering a matching program as a method to improve the internship process for students, internship committee members, and academics and address barriers and obstacles of the process previously identified in other studies (Boles et al., 2024; Sisk et al., 2023). There is a need to replicate the pilot, both in SEACLP and larger groups, and gather information on the longitudinal outcomes of a regional internship matching program, such as success of internship acquisition and retention of aspiring professions in the region. In addition, the findings highlight the value of communication in the internship process. Internship and academic sites should provide clear, detailed, and honest communication to students so that they can navigate the internship process with ease and confidence. Furthermore, the study demonstrates the potential outcomes for collaborations between academic and clinical sites, suggesting such collaborations ought to be pursued to expand the process of internships.

Conclusion

This convergent parallel mixed-methods study examined the outcomes of a regional matching program for child life internships. Overall, the matching program was found to be successful, as indicated by the high rates of satisfaction and indications of wanting the matching program to continue in the region. Specifically, students, internship coordinators, internship committee members, and academic coordinators reported benefits of the matching program to include optimizing time, lessening the cognitive and emotional load of the internship application, and supporting the value of communication during the process. After many years of questioning how a matching program might work in child life, this study exploring a matching program in child life is the first of its kind. The findings suggest that a regional internship matching program can be successful in child life and should continue to be explored.